John Courtney Murray

(8 of 10)

But America was a different kind of revolution. In some ways, as Murray puts it, it was not a revolution but a conservation, in that it revived the old freedom of the church. After the colonial phase of religious fanaticism—of setting up state churches and exiling heretics—the early Americans seemed more interested, with the First Amendment, in providing for the freedom rather than the restriction of religion. Catholics knew that a new era had begun when in 1783 the Vatican asked the Continental Congress for permission to establish a U.S. bishopric and was told that, since the matter was purely spiritual,

Congress had no jurisdiction. For the first time in centuries, the Catholic Church was free to work and witness as it saw fit, without special privileges but also without requiring a whole chain of consent from secular government.

New Commonwealth. American pluralist society was a new kind of commonwealth—a nation under God but forcing no one to worship in a particular manner, not because religion was considered unimportant or merely a private affair, but because it was thought that God is best honored by free men. As Roger Williams wrote: "There goes many a ship to sea, with many hundred souls in one ship . . . Papists and Protestants, Jews and Turks ... I affirm that all the liberty of conscience, that ever I pleaded for, turns upon these two hinges—that none of the Papists, Protestants, Jews, or Turks, be forced to come to the ship's prayers or worship, nor compelled from their own particular prayers or worship, if they practice any."

While the Catholic ideal was—and is—a ship of state in which all acknowledge the One True Church, U.S. Catholics soon realized that the unique U.S. situation gave them unprecedented freedom to grow. In 1884 the Roman Catholic Third Plenary Council of Baltimore declared: "We consider the establishment of our country's independence, the shaping of its liberties and laws, as a work of special Providence, its framers 'building better than they knew,' the Almighty's hand guiding them."

Under the freedom and protection of the First Amendment, the Catholic Church has flourished in America. The statistics are impressive: the Catholic population increased from 1,767,841 in 1850 to 40,871,302 in 1960, four times faster than the American population as a whole. But the new situation of Catholics in the U.S. is much more than figures. The church of 50 years ago was largely a church of immigrants, whose concern was to protect and build their minority religion in a Protestant land while showing their fellow Americans what all-out patriots they were. Today, an increasing number of well-educated and theologically sophisticated young Catholics are beginning to take part in what Father Murray calls "building the city"—contributing both to the civic machinery and the need for consensus beneath it.

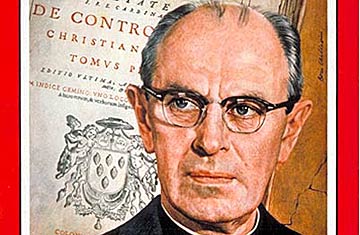

Debate & Dramatics. The Rev. John Courtney Murray, S.J., is unquestionably the intellectual bellwether of this new Catholic and American frontier. He is peculiarly well fitted for this role—by intellect, by temperament and, just as important, by a life that has been largely insulated from the psychosociological problems of the Catholics in the U.S.

John Courtney Murray was born 56 years ago on Manhattan's then fashionable