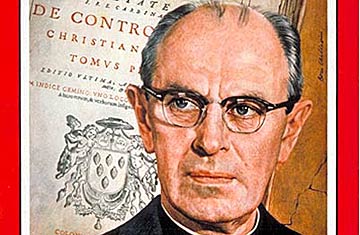

John Courtney Murray

(5 of 10)

How does natural law apply to some of the larger practical issues of the day? An example is the use of force, which, says Murray, baffles Protestant morality. (The "Eastern seaboard liberal," he says, at once abhors and adores power, since in the matrix of American Protestant culture "power is unconsciously regarded as Satanic.") Old-line Protestant ethics saw social morality as personal morality writ large, which led to such inappropriate questions as "How does one apply the Sermon on the Mount to foreign policy?" This failure to understand the difference between public and private morality, argues Murray, leads to the disastrously false alternatives that often characterize U.S. foreign or military policy, e.g., sentimental pacifism or all-out atomic holocaust. Murray believes that there is morally valid territory between these extremes, that war may be legitimate in the defensive repression of injustice, and that the concept of limited war has moral significance. In general, says Murray, Americans should learn from the natural law tradition that "policy is the meeting place between the world of power and the world of morality."

The New Rationalism. What is the non-Catholic to make of natural law? The Founding Fathers certainly accepted the concept, in one form or another, much of it having reached them through the English common law out of the vast reservoir of Christian tradition. Murray thinks that the Bill of Rights was far less a "piece of 18th century rationalist theory [than] the product of Christian history." In fact, to some it may seem that Murray at times regards the U.S. as having sprung directly from medieval Christianity—he calls St. Thomas "The First Whig"—with hardly any help from Protestantism or the Enlightenment.

But the main source of natural law to the early republic was of course John Locke, whose version of it was radically different from the Catholic view. Where the Catholic theory sees society as equally given with the person, Locke regarded society merely as something for the convenience of the autonomous individual and not inherent in the nature of man. Murray condemns Locke as too much of an individualist to have "any recognizable moral sense" of the rights of man: "There is simply a pattern of power relationships." Still, when pressed, Murray concedes that Locke's natural law is better than no natural law at all, and throughout much of U.S. history, the concept appeared in the courts and in government.

What caused its decline is chiefly a combination of Protestant theology and modern rationalist philosophy. "The new rationalism," as Murray describes the thought of men like John Dewey and Bertrand Russell, sees man as autonomous, beneath no knowable God, with a