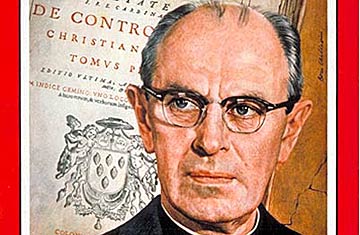

John Courtney Murray

(2 of 10)

Debating issues of church and state during the 1960 campaign, Catholics sometimes sounded defensive. Not so John Courtney Murray. His lifelong subject of study has been the interaction of America and Catholicism; some critics in his own faith have occasionally held him to be more American than Catholic. Without representing an ' official position—and without running counter to it—he is now telling his fellow Catholics that they must become more intellectually aware of their ' coexistence'' in a pluralist, heavily Protestant society. But not even remotely is he trying to trim Catholicism to any other faith, or to the absence of faith. In his view, Catholics can make a major contribution—perhaps the decisive contribution—to an American society in spiritual crisis. His terms may startle some non-Catholics. "The question is not," says Murray, "whether Catholicism is safe for democracy, but whether democracy is safe for Catholicism."

The Separation. Most Americans, when they hear about conflicts between "church and state," think of certain concrete issues that reach the headlines. On most of these, Murray has taken liberal and eloquent positions. Item: on government funds for parochial schools, he thinks simple justice demands it, but argues that Catholic pressure for it should be confined to argument and slow persuasion. Item: on censorship, he upholds the right of the church to guide its own faithful and to convince others with its moral judgments, but by persuasion, not boycotts. There is danger, he suggests, in reading bad books, but also "great danger in not reading good books."

Father Murray is generally in favor of the U.S. version of church-state separation, established by the First Amendment and by the principle that government and church function in entirely separate spheres, one caring for the people's earthly wellbeing, the other endowed with the mission of guiding them toward salvation. This, argues Murray, is an ancient Christian principle, even if often broken by either church or state in less socially and juridically advanced times. Writes Murray: "In 800 A.D., Leo III had a right to crown Charlemagne as Emperor of the Romans; but this was because it was 800 A.D. If there were a Christendom tomorrow—a Christian world-government in a society whose every member was baptized —the Pope, for all the fullness of his apostolic authority, would not have the slightest shadow of a right to 'crown' so much as a third-class postmaster."

But such matters of church and state are all part of a larger issue, as Murray sees it. That issue is the American public philosophy,