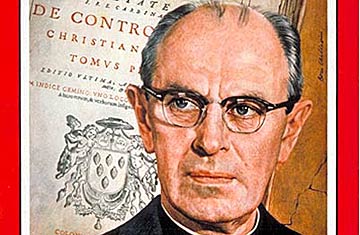

John Courtney Murray

(3 of 10)

The Noes Have It. Is there an American consensus? That there was one once is not in doubt. The Founding Fathers knew what they believed and what they wanted for their new Land of the Free, and they carried on their civil argument in terms they shared. What Historian Clinton Rossiter calls the "noble aggregate of 'self-evident truths' "—as expressed in the Declaration of Independence and later in the Bill of Rights—essentially added up to liberty under limited government, guided by law and ultimately relying on God. The builders of the republic knew what they meant by liberty, by law and by God; less obviously but just as importantly, they knew what they meant when they declared, "We hold these truths." They believed that ultimate, universal truth could be perceived by human reason. They also believed, in Murray's words, that "only a virtuous people can be free," that freedom can survive only if the people are "inwardly governed by the moral law."

If there is anything left of this consensus, thinks Father Murray, it is not the doing of U.S. philosophers, most of whom are positivists—whose strictly limited truths must be capable of scientific proof—or pragmatists—whose truths are whatever works. Says Murray: "The American university long since bade a quiet goodbye to the whole notion of an American consensus, as implying that there are truths that we hold in common, and a natural law that makes known to all of us the structure of the moral universe in such wise that all of us are bound by it in a common obedience."

When he talks to academic audiences about an American consensus or, as he sometimes calls it, "the public philosophy," Father Murray is usually greeted by a blank stare or emphatic denial that such a thing exists. "Sir," someone is sure to say, "you refer to 'these truths' as the product of reason; the question is, whose reason?" When Murray replies that it is not a question of whose reason but of right reason, the rejoinder is: "But whose reason is right?"

Thus, to the question of whether an American consensus exists today, Father Murray feels that the noes have it. But, says Father Murray, ask if America needs a consensus and the yeas have it.

New Act of Purpose. Murray poses his question cogently: "Can we or can we not achieve a successful conduct of our national affairs, foreign and domestic, in the absence of a consensus that will set our purposes, furnish a standard of judgment on policies, and establish the proper conditions for political dialogue?" Anti-Communism is a poor substitute. If Communism should vanish overnight, he says, Americans would still