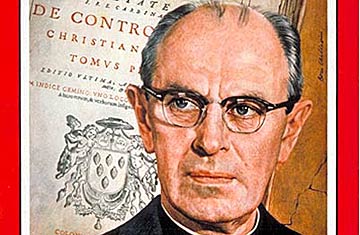

John Courtney Murray

(6 of 10)

While Murray concedes that natural law has been used vaguely, naively and repressively, he sees far greater danger in the "subtle and seductive system" by which all ethics are considered relative.

In Time of Trouble. Many Protestant theologians are critical of the formal rigidity of the natural law theory; neither they nor the Jews find the stock Biblical proof-text from St. Paul convincing.* Others, notably Karl Barth, reject the Thomist theory of analogy on which the natural law stands; in fallen man, they hold, sin has shattered God's image, and since the Garden of Eden he has had no direct knowledge of God's reason or his will without revelation. Many Protestants distrust the whole Scholastic tradition, which they feel keeps man from direct contact with God by interposing an artificial structure of reason. But some Protestant theologians, while far from accepting the classical Catholic version, are ready to underwrite natural law in some form. Reinhold Niebuhr denies the existence of natural law but concedes "certain laws, certain norms and degrees of universality'' (incest, for instance, is almost universally taboo).

Father Murray feels that only inside the Catholic community has natural law endured, therefore Catholic participation in the U.S. consensus has been "full and free, unreserved and unembarrassed, because the contents of this consensus—the ethical and political principles drawn from the tradition of natural law—approve themselves to the Catholic intelligence and conscience. Where this kind of language is talked, the Catholic joins the conversation with complete ease. It is his language. The ideas expressed are native to his own universe of discourse. Even the accent, being American, suits his tongue."

The 1960 election of a U.S. President from the Catholic community dramatizes this claim. And whether or not the Catholics have been the true custodians of the American consensus, as Murray would have it, there is no denying that a new era has begun for Catholics in America, a country that in itself represents a new era in the history of church and state.

Two There Are. The idea that religion and government are different—let alone separate—is a relatively new one. Either the ancient kings were sacred, if not actually gods, or the high priests exercised kingship, as in Israel. Separation began with the concept of an official religion (Plato recommended in his Laws that all citizens who refused to accept the state religion should be imprisoned for five years, each day of which they should listen to a sermon). Christianity became a state religion 347 years after