John Courtney Murray

(7 of 10)

Then began Europe's long up-and-down battle between Pope and Emperor, with the Emperor usually ending up on top. Monarchs customarily appointed bishops in the Middle Ages; when Pope Gregory VII told Emperor Henry IV to stop doing it and was refused, he excommunicated Henry, and had the warming pleasure of keeping the penitent Emperor waiting barefoot in the snow at Canossa for three days before letting him in for forgiveness. But Gregory's fun was soon over. Henry exiled him in 1084, and the back-and-forth went on.

Basic Catholic doctrine on the ordering of society was laid down by Pope Gelasius I in a letter to the Byzantine Emperor Anastasius I in 494: "Two there are, august Emperor, by which this world is ruled on title of original and sovereign right—the consecrated authority of the priesthood and the royal power." This, says Father Murray, established a "freedom of the church" in the spiritual sphere that served to limit the power of government on the one hand, and on the other brought the moral consensus of the people to bear upon the King.

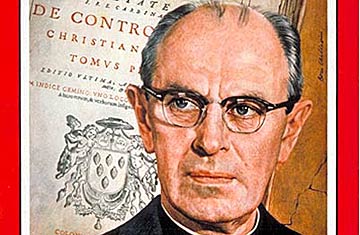

But with the rise of the absolutist monarchies in the 17th century, Gelasius' finely balanced dyarchy was shattered. Between Pope and King stood a saint who took 309 years to be canonized, Robert Francis Romulus Bellarmine (1542-1621), whose influence reached far beyond his lifetime. His was a time of upheaval; Galileo was turning the old earth-centered cosmos upside down, a new national consciousness was breaking up the Holy Roman Empire, and the "heresy" of Protestantism was digging in throughout the world. As one of the greatest polemical theologians in his church's history, Jesuit Cardinal Bellarmine was in the forefront of the struggle against the Protestants. But within Catholicism he was a transitional figure, facing the modern era with his feet firmly rooted in the Middle Ages. And. like many another human bridge, he was trampled on from both sides.

The temporal authority of the Pope was under challenge by Europe's new rulers, and Cardinal Bellarmine earned the enmity of ecclesiastical conservatives (notably Pope Sixtus V) by maintaining that papal jurisdiction over heads of state was only indirect and spiritual—the position generally accepted today. On the other hand, in opposition to the Scottish jurist Barclay, he denied the divine right of kings, for which one of his books, De potestate papae, was publicly burned by the Parlement of Paris.

Different Revolution. In the long run, it was the supporters of state power who won out against the champions of church power. In the words of Father Murray, the Gelasian principle of "two there are" became "one there is"—one increasingly powerful state. From absolutist monarchy, Murray sees a straight line of development to modern "totalitarian democracy" via the French Revolution's Jacobin republic, which put the civil government in almost complete control of church affairs. To this day, French separation of church and state makes Thomas Jefferson's famous "wall" look like a split-rail fence.

The French example, feels Murray, became the model of monism—the political theory that "regards the state as a moral end in itself."