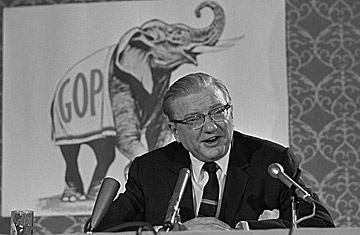

GOP National Chairman Ray Bliss

(4 of 10)

Ideologically too. But RONALD REAGAN, 55, has been moving toward the middle ever since he announced his candidacy and has been trying to prove that, unlike Barry Goldwater, he can be a kind of ecumenical conservative. After the 1964 election, he bitterly denounced Republicans who failed to support Goldwater as "traitors"—an appellation that included, among others, Rockefeller, Brooke, Michigan's Governor George Romney, Senator Jacob Javits of New York and Clifford Case of New Jersey. But after his nearly 1,000,000-vote victory last week, Reagan emphasized "how foolish it is to be separated by labels, how much we really have in common." Reagan may also have been somewhat sobered by the fact that his moderate running mate for Lieutenant Governor, Robert Finch, Nixon's 1960 campaign manager, ran nearly 100,000 votes ahead of him and that the Democrats won control of both houses of the state legislature—though by reduced majorities.

What surely will temper Reagan is the job he will take on next January. The task of running the most populous state in the Union, accommodating the 1,000 new arrivals who pour in daily, satisfying California's insatiable demands for more schools, roads, hospitals and—not least—water, demands an activist Governor. However great the momentum of past programs, the impetus of growth in such states as New York and California has invariably proved greater. Actually, though he has promised to cut back on wasteful state programs, Reagan admits that his "creative society" will not come cheap.

Situated between Rockefeller -and Reagan—geographically as well as ideologically—is Michigan's GEORGE ROMNEY. A powerful speaker, Romney tirelessly emphasizes the Democrats' "destructive centralism," urges Republicans to begin "revitalizing state and local governments," but so far has had little to say on most national and international issues. Though he was expected to win a third term, few experts anticipated the extent of his victory. Before the election, Wisconsin's Melvin Laird, chairman of the House Republican Conference, observed cagily that to become a serious presidential contender, Romney would not only have to win reelection by a heavy margin but would also have to carry G.O.P. Senator Robert Griffin and a couple of doubtful Congressmen in with him.

Romney surpassed even that herculean task. He amassed a 570,000-vote plurality, pulled Griffin in despite a formidable challenge from former six-term Governor G. Mennen ("Soapy") Williams, helped return five Republican underdogs to Congress, was instrumental in establishing G.O.P.