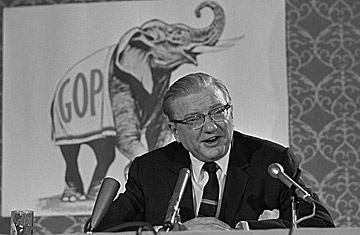

GOP National Chairman Ray Bliss

(3 of 10)

End of Consensus. To G.O.P. Chair man Bliss, the "acid test" for Republicans came at the bottom—the state legislature races. Previously, the party had outright control of only five state chambers; now it controls 17, shares control with the Democrats in eight others. Nationally, a key G.O.P. target was the group of 48 Democratic freshman Representatives who had won traditionally Republican seats in 1964; only 21 survived. By slashing Johnson's 155-vote Democratic cushion to 61, the Republicans actually deprived him of an effective majority, since some 90 Democratic Representatives are Southerners whose allegiance to the party program is highly selective. Thus, he has even less room to maneuver than John F. Kennedy had after 1962; though the election that year left him with an 83-vote majority, Kennedy's last days were plagued by a curmudgeonly, uncooperative Congress.

Without doubt, the more conservative cast of the 90th Congress will force Johnson to abandon any remaining hope of consensus politics—which, paradoxically, could work to his advantage. With his craving for universal approval, the President sought to please everybody at once, a feat that seemed almost possible with his huge congressional majority. Now, forced into a more partisan position by a reinvigorated opposition, he will have to risk offending one group or another, and though this may cost him some legislative battles, he might win back some esteem at the same time.

Performance First. Significant as its gains in the House may be, the G.O.P.'s future hopes rest, in all likelihood, on its victorious Senators and Governors. With 30 G.O.P. seats in contention at the two levels, the party lost only two, the supposedly safe statehouses in Maine, where Kenneth Curtis ousted twice-elected Republican Governor John Reed, and in Kansas, where Democrat Robert Docking parlayed petulance over a $54 million tax boost into an upset over Governor William Avery. While the party was successfully defending its other 13 governorships and 15 Senate seats, it wrested ten statehouses and three Senate seats from Democratic hands. Most significantly, the rich harvest of victories gave the party a whole new cast of charismatic personalities—along with a few old ones that were newly rejuvenated by success.

Six of them stand out in particular—a trio of Governors who personify the party's diversity, and a senatorial threesome whose pragmatic, performance-first philosophies promise to infuse new vigor into the undermanned G.O.P. Senate wing.

Triple Mainstream. Among the Governors, New York's NELSON ROCKEFELLER, 58, scored the most sensational upset. Six months ago his popularity was at an alltime low. He insisted nonethe less on running for a third term. "Why do you do it?" one of his brothers asked him. During the campaign, most polls seemed to justify the fraternal concern.

On election night, Democratic Challenger Frank O'Connor dined on Oysters Rockefeller, but battling Nelson savored a more sumptuous dish. He won by 400,000 votes in a four-sided race, scoring so impressive a victory that a newsman asked whether he still planned to honor his pledge not to seek the presidency again. "Yes sir," replied Rocky. "Unequivocally." What he does aim to do is "to play a role" in