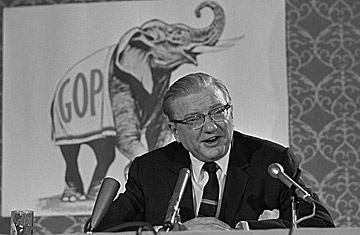

GOP National Chairman Ray Bliss

ELECTIONS

Sitting back in a Washington hotel room, Republican National Chairman Ray Bliss smiled the kind of smile that had hardly creased his face in two years. "This press conference," he said, "will be a little different from my first one, when you were asking me if the Republican Party would survive." If that question seemed germane in the wake of Lyndon Johnson's 1964 landslide, it was definitively answered last week. "It looks to me," beamed Bliss, "as if we have a very live elephant."

He—and the elephant—had every reason to trumpet. With a record 56 million voters (48% of all voting-age Americans) casting midterm ballots, the G.O.P. scored solid gains at every level, from state assembly to U.S. Senate. It picked up some 700 seats in the state legislatures, more than erasing the 529-seat loss of two years ago. Having lost 38 House seats in the Goldwater debacle, the Republicans scored a net gain of 47, their best showing in two decades and a marked improvement over the average off-year pickup of 38 seats for "out" parties during the past half century. The G.O.P. won three additional Senate seats and made major inroads in the gubernatorial races. With an overall gain of eight governorships, the Republicans now take possession of 25 of the nation's 50 statehouses—and could even make it 26 if their candidate eventually wins Georgia's disputed election.

Among the seven most populous states, Republican Governors were elected in all but Illinois and Texas, now hold the top spot in California, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Michigan, which between them have 159 of the 270 electoral votes needed to pick the next President. Moving to establish itself as the party of all the people, the G.O.P. made deep inroads in the historically sacrosanct Democratic strongholds—the cities—with significant gains in New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Detroit, Chicago, and Los Angeles.

Back from the Brink. The Republican recovery was the most dramatic since 1938. Then, after Franklin Roosevelt's unprecedented sweep in 1936 had given the Democrats fantastically bloated congressional majorities—333 to 89 in the House, 75 to 17 in the Senate—the G.O.P. rebounded and recaptured 80 seats in the House and six in the Senate. The 1964 Goldwater rout left the G.O.P. on the short end of a 295-to-140 count in the House and a 67-to-33 margin in the Senate. Dick Nixon overstated the case only slightly when he warned: "This is the year the Republican Party either goes up or goes out."

The victory did more than pull the G.O.P. back from the brink. It reestablished an effective opposition in Congress, giving the two-party system some badly needed adrenalin. It also erased the Goldwater image of a narrow, negative clique, replacing it with the vision of a cohesive, inclusive party broad enough to encompass men as ideologically diverse as New York's Nelson Rockefeller on the left and California's Ronald Reagan on the right. It is broad enough, too, not only for a polished politician with the all-American looks of Oregon's Senator Mark Hatfield or a self-made millionaire like Illinois' Senator Charles Percy, but also for the first popularly elected Negro Senator in U.S. history, Massachusetts' Edward Brooke*: for the son of Greek immigrants, Maryland's