(7 of 17)

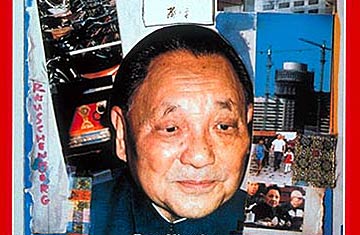

Now Deng and his lieutenants think the time has come to take a much longer step toward a full-fledged market system. Under a plan that went into effect in late 1984, state industry is also run under a contract system. Central planners still set broad production goals, but they directly assign only a portion of raw materials and distribute at fixed prices only a set quota of a factory's output. Managers otherwise are allowed and even required to line up their own suppliers, decide for themselves what to make beyond the goods that must be sold to the state and find buyers for the merchandise at prices that can fluctuate. They pay a 55% corporate income tax and keep the rest of their profits to use for reinvestment, bonuses and social welfare such as housing, medical care and recreation. Most investment capital is still supplied by state-owned banks. But managers have to compete for loans, and pay interest of 5% (up from 1% as recently as the late 1970s).

The avowed goal is to replace "administrative planning"--that is, direct orders on what and how much to produce--with a looser system of "guidance planning." Central planning, explains Huan Xiang, director general of Peking's Center for International Studies, "seriously hampered the initiative and creativity of enterprises and workers and to a great extent emasculated what would otherwise have been a vigorous economy. The more centralized, the more rigid; the more rigid, the lazier the people; the lazier the people, the poorer they are." Managers now are supposed to hustle in response to the same signals--interest rates, market demand, prices, profit--that guide Western businessmen. And just as the state will no longer take all profits, it will eventually stop subsidizing losses. Deng's planners bluntly assert that they are prepared to let inefficient state enterprises go bust.

This ambitious scheme has got off to a somewhat stumbling and chaotic start. State bankers at the end of 1984 overused their new authority and went on such a wild lending spree that the People's Bank of China, the country's central bank, had to tell them to stop. Factory bosses, in contrast, widely complain that they are still waiting for confirmation from local party and government officials that they can begin exercising the new freedoms they supposedly were granted at the start of 1985. For the first time, Deng is proposing to crimp seriously the powers and privileges of tens of thousands of national, provincial and local party bosses who are accustomed to exerting life-and-death authority over the economy. Ominously but not surprisingly, many seem to be dragging their feet, if not blocking the reforms outright.

Some popular opposition is developing. To give the nascent market system a chance to work, Peking abolished some subsidies for food, clothing and utility production and gradually freed some industrial prices. One result was a whiff of that old capitalist evil, inflation: in some cities, food prices jumped 35% in early 1985. The blow was softened by a continuation of wage increases begun immediately after Mao's death. Nonetheless the price boosts stirred widespread grumbling, particularly among older Chinese who retain bitter memories of the hyper-inflation that preceded the Communist takeover in 1949.