(15 of 17)

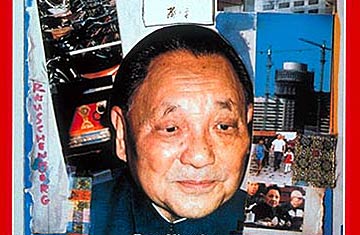

There is no reason to doubt Deng's own commitment. "This is the only road China can take," he told TIME. "Other roads would only lead to poverty and backwardness." At a Communist Party conference in September, Deng and his allies succeeded in getting supporters of the reforms promoted to many high- and mid-level positions in the government and the party. Deng, says a Western analyst, "has prepared not only his own succession but the succession below that as well."

But that same party conference provided a striking indication of the depth of the opposition Deng faces in the form of a speech by Chen Yun, 80, a Politburo member who likens the economy to a bird that must be kept in a cage. "A planned economy must remain as our primary goal; a market economy can only be a supplementary measure for temporary adjustment," said Chen. More generally, he complained that "everything for money is the decadent capitalist idea which has gradually prevailed in our party and society." Even if that point of view should eventually win out, a return to full-fledged Maoism seems most unlikely. The sufferings of party officials and intellectuals during the Cultural Revolution, the economic stagnation under Mao and the rapid growth achieved during the first stage of Deng's policy all argue against it, even to Chen and other conservatives. On the whole they approve of Deng's rural reforms.

Yet it is possible to foresee a crackdown after Deng passes. Support for greater central control of the economy could come from party officials fearful of losing control and from ordinary citizens envious of the new rich class. The Chinese press already reports many stories about this "red-eyed disease," like one about a peasant woman who poisoned all the ducks of a prosperous neighboring farmer.

The deciding factor undoubtedly will be the further success, or lack of it, of the reforms. Deng's formula for overcoming opposition is a simple one: leave the critics alone and let them see for themselves that the system works and that they would be better off if they went along. "We will let practice dissipate their worries and misgivings," he says.

But success cannot be taken for granted either. Along with growth, the reforms have produced some "evil winds," as the Chinese call them. The most ominous is an upsurge in bribery, black-marketeering and other forms of corruption. Chen Yun reported that in the past year alone party and government officials or their children have started 20,000 private businesses, "a considerable number of which collaborate with lawbreakers and unscrupulous foreign businessmen" to get rich in ways that are decidedly not glorious. Among the crimes he accused them of were peddling counterfeit medicine and "the sale of obscene videotapes." It is widely estimated that about half the managers of state-owned enterprises pursue profit by cheating on corporate income taxes. The most sensational scandal involved a ring of party and government officials on Hainan Island who sold $1.5 billion of goods illegally imported through Hong Kong, including Mercedes limousines and color TV sets, before they were caught. It is at least possible that conservatives can muster support for the idea that the only way to stamp out corruption is to cut back on modernization.