(4 of 17)

That something has failed, and failed badly, is no longer seriously disputed, even by many Marxist experts. Before Deng, the failure was more starkly obvious in China. The average peasant or city worker was little better off, if at all, when Mao died in 1976 than he or she had been in the 1950s. But even the Soviet Union has long since had to forget Nikita Khrushchev's hollow boast that it would inevitably "bury" the U.S. by surpassing the American standard of living. Quite the opposite: the U.S.S.R.'s economic growth rate has slipped to about half the pace of the 1960s, and its citizens still have to stand in long lines for such minor amenities of life as toilet paper and detergent powder. On the most basic level, Moscow must import huge tonnages of grain from the capitalist world to keep the Soviet populace properly fed.

Gorbachev has been unsparing in his criticisms of Soviet economic performance. "You squander countless resources in every industry," he told party workers in Leningrad last May. But so far he has been unwilling to modify in any essential way the system of centralized state control of every aspect of economic life fashioned by Joseph Stalin; he has been trying only to make it work better. While promising to "restructure" the economy, Gorbachev pointedly avoids using the word reform, apparently because it implies a more drastic change than any he is ready to contemplate.

In practice, Gorbachev's program so far consists largely of public scolding of inefficient industry managers and incessant calls for "discipline" and "imaginative, honest and conscientious work from every individual, from worker to minister." His most striking measure to improve productivity has been to crack down on alcoholism by restricting production and consumption of vodka and other spirits.

Gorbachev is extending experiments to give selected industrial and farm managers slightly greater freedom in pricing and production decisions. His closest economic adviser, Abel Aganbegyan, has called for a reallocation of investments to modernize factories rather than build new ones and to improve the quality of products. But this rechanneling is to be carried out by the central planners. So, as Gorbachev suggested in his August interview with TIME, his program rather contradictorily appears to call for a loosening of state control in some areas and a tightening in others--at the same time.

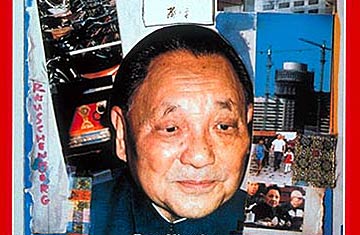

Deng, shortly after emerging from his third period of disgrace and returning to power in 1978, faced squarely the heretical thought that the system of state control was itself the problem. He set about to replace it with a hybrid not quite like anything seen before. The Chinese system is still so new that it does not have an agreed name. Outside analysts often call it "market socialism," and some Chinese speak of creating a "commodity economy." Deng's formulation is a rather uninspiring "socialism with Chinese characteristics." But then Deng, a thoroughgoing pragmatist, has never been much for labels. His most celebrated saying is a homely metaphor to the effect that it does not matter whether a cat is black or white so long as it catches mice.