(12 of 17)

In matters of economic organization, however, even Lenin was a backslider of sorts. In 1921, when his "war Communism" stirred dangerously strong opposition, he shifted to the New Economic Policy, which sounds almost like a preview of Deng's reforms. Under the N.E.P., the new Soviet state owned and operated only what Lenin called the "commanding heights" of the economy, that is, the basic industries. Peasants could grow and sell privately what they wished after paying a tax in produce to the state; small-scale private enterprise was permitted; foreign capital was invited in.

But while Deng intends his reforms to be permanent, Lenin viewed the N.E.P. as a strategic retreat. Stalin put an end to it and launched the Soviet Union on a nearly total collectivization of agriculture and nationalization of industry. Stalin's system became the dominant version of Marxism, if only because the U.S.S.R. for decades was the sole significant officially Marxist state and remains its most powerful one.

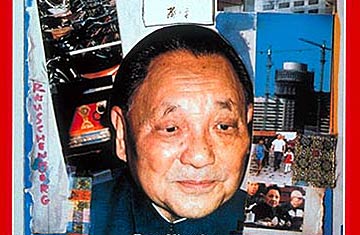

One of Mao's main contributions to Marxist theory was to stress the role of the peasants, rather than the industrial workers exalted by Marx. Another was the doctrine of perpetual revolution, which reached chaotic extremes during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution that began in 1966. Party bureaucrats and intellectuals were banished to factories and into the countryside to "learn from the people" by working with their hands, and teenage Red Guards rampaged through China assaulting supposed "bourgeois rightists." One was Deng, who was paraded through Peking with a dunce cap on his head and mocked as a "capitalist roader."

He is not exactly that, but to the extent that he bothers with ideology, which is not very far, he certainly tends to a minimalist definition of Marxism. As Deng told TIME: "In carrying on socialism, I think we should uphold two things. First, public ownership should always play a dominant role in our economy. Second, we should try to avoid [class] polarization and we should always keep to the road of common prosperity." Beyond that, he implies, pretty much anything goes if it "will lead China to development."

Chinese intellectuals are engaged in a spirited debate about just what can be accommodated under a Marxism stripped to its barest essentials. The sale of stock in a business? Yes, says one theoretician, as long as the shares are bought by employees, or possibly their neighbors if an enterprise happens to be a collective (a few of which have in fact sold shares). An exchange on which employees and neighbors could trade the shares among themselves? "That is under study." A social scientist specializing in Marxist ideology goes so far as to suggest that since Marxism-Leninism purports to be a science, even nonparty people should have the right to re-examine it. Says he: "Science belongs to everybody."