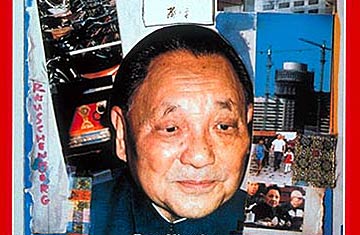

The leader of 1 billion Chinese was joking, of course; he lost part of the hearing in one ear long before he launched the world's most populous nation on an audacious effort to create what amounts almost to a new form of society. But, as might be expected from the diminutive (4 ft. 11 in.), steel-hard Deng, 81, it was a joke with a sharp point. If in his more solemn moments he still attempts to justify what he often calls his "second revolution" in the name of that patron saint of Communist revolution, Karl Marx, Deng is well aware that the system he is evolving in China either ignores or defies many of the precepts most cherished by traditional Marxists (especially those running the Soviet Union). In the Chinese spirit of balance between yin and yang, Deng's second revolution is an attempt on a monumental scale to blend seemingly irreconcilable elements: state ownership and private property, central planning and competitive markets, political dictatorship and limited economic and cultural freedom. Indeed, it is almost, or so it often seems to skeptics in both the Western and Marxist worlds, an attempt to combine Communism and capitalism.

It is also a high-risk gamble. The elements may prove truly irreconcilable, and Deng's bold experiments could dissolve into economic chaos. It is even possible that they could give way, though probably not until after his death, to at least a partial restoration of the ironfisted, xenophobic rule and extreme regimentation imposed on China by Deng's predecessor Mao Tse-tung. But in 1985 Deng gave fresh evidence of his determination to push his reforms through to their conclusion, whatever that might be. Having essentially completed a transformation in the countryside, where 80% of China's masses live, by freeing peasants to grow what they wish and to start private businesses, Deng concentrated on what may be the harder job of bringing change to China's cities and requiring the managers of state-owned enterprises to behave like profit-hungry, innovative capitalists.

Whether this second stage of the second revolution can fulfill Deng's dream of hauling China out of its still desperate backwardness into the 20th century by the time the century ends is anyone's guess. It got off to a somewhat rocky start, and is encountering more opposition than the first, rural stage did. But if it should succeed, the transformation would have profound and enormous consequences throughout the world.

The Soviet Union, which has historically feared the Chinese masses on its southeastern border, would face a neighbor considerably strengthened by a triumphant heresy. Communists everywhere, notably in the Third World, would see an alternative to the failures of Soviet-style Marxism. Many of China's neighbors in the Far East, including Taiwan and South Korea, would find that a political foe had been tamed into a trading partner, while an economic weakling had become a mighty competitor. Most important, perhaps, the U.S. and other Western countries would see the crusading faith that has made the Marxist third of the world an enemy converted into a system that the West could live with and in some respects, though certainly not all, applaud.