(13 of 17)

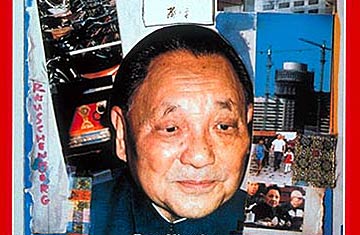

At the minimum, the spirit of Deng's course is very different from that of classic Marxism. While Marx can be read as allowing the market to coexist with socialism for a while, he regarded the market as an exploitative device that would eventually disappear. It seems doubtful that he would have approved any attempt to revive it after it had disappeared. Most of all, Deng's version of Marxism lacks the crusading zeal of the classic variety. Marx preached his revolution as history's final showdown between the forces of light and those of darkness. It strains the imagination to conjecture what he might have thought of a second revolution that seeks, in Deng's words, "to adopt useful things [from] the capitalist system."

Oddly, though, the guardians of Marxist purity in Moscow are not making anything like the case against Deng that might be expected. In private, they fear that China will be come an even greater military threat if the reforms succeed. But in public, Soviet journals have noted China's economic progress and expressed only mild doctrinal qualms. The Soviets must avoid name calling if they want to continue smoothing political relations with Peking. Also, suggests an Asian diplomat in Moscow, they "may want to keep their options open in case they decide, five years from now, that they want to try some of these things themselves. They will not be inviting capitalists into special economic zones, perhaps, but they might be interested in a 'managed' market system."

Soviet officials scoff at the idea that there is anything the highly industrialized U.S.S.R. could learn from agrarian China. But they have at least been inquisitive about Deng's reforms, and by some indications more impressed than they like to admit. Dwayne Andreas, chairman of Archer Daniels Midland Co. (a giant U.S. corporation dealing in farm produce) and a frequent visitor to China, journeyed to Moscow in 1984 and had a two-hour private talk with Gorbachev, who was then still in charge of Soviet agriculture. "He was very curious about what I told him concerning the reforms," Andreas recalls. "He particularly wanted to hear how China's joint-venture system with foreign companies worked."

Long range, though, the prospect of China's creating a modern society by following a heretical brand of Marxism constitutes a deadly ideological danger to the Soviets. They are having enough trouble as it is getting their allies, not to mention Communist movements that have not yet come to power, to follow their leadership. China's example can only encourage such countries as Yugoslavia and Hungary to continue their efforts to blend market elements into state-dictated economies, and lead out-of-power Marxist parties to think they do not have to copy the Soviet line either.