(16 of 17)

The reforms could fail in other ways too. Industry managers have never been trained in the complex skills needed to make a market economy work. Indiana University's Hans Thorelli, who served as a visiting professor of marketing in Shanghai and Dalian in the early 1980s, recalls being asked in all earnestness by his students, "What is a salesman?" There is always the threat, too, that population growth will swallow up any production increases.

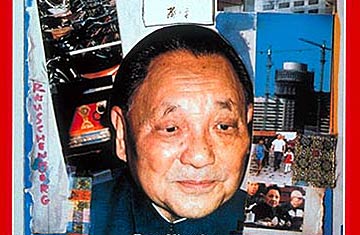

A deeper question is whether Deng can bring himself, and lower officials, to free the market enough for it to work properly. Werner Gerich, 66, a West German manager who was hired to run a state-owned diesel-engine plant in Wuhan, found his factory, like many others in China, heavily overstaffed. "If I fired 700 people [out of a total of 2,140], we could make the same number of engines with better quality because we would have money," he says. But he quit in despair because party officials would not let him make that and other changes he considered essential. Mao's tradition of "the iron rice bowl"--that is, lifetime employment--dies hard.

One top economic official in Shanghai gives this reason for retaining at least some production quotas: "Of course we cannot give each factory the right to decide what to produce. What would happen if all of our garment factories produced blue jeans and none produced coats?" The capitalist answer would be that a free price system would prevent that. The price of jeans would plummet, and the price of coats would soar; many jeansmakers would, so to speak, lose their shirts and be happy to switch to turning out coats. But Deng and his planners seem unwilling to let prices fluctuate freely enough to guide investment decisions in that manner.

The deepest dilemma is whether China can achieve even the relatively free economy Deng is trying to create without undermining Leninist control of politics and society. There are many Chinese, not all Chen Yun types, who doubt that, in the long run, economic freedom can exist without greater political liberty. They are already debating what course the nation will take if they are proved right.

One Chinese social scientist states the dilemma pithily. Says he: "If the party does not continue the reforms, the economic situation will get worse. But if the reforms continue, the party itself will lose power" to newly rich peasants and newly independent factory managers. His conclusion is that the party will cut back on, if not reverse, the reforms rather than let that happen. But Zhao Fusan, a senior scholar at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, states flatly that "the process of economic reforms will naturally bring about a process of democratization, the setting up of checks and balances in political life and the rule of law." If so, and if the Chinese are willing to reinterpret Lenin as well as Marx, the potential consequences for both the Communist and non-Communist worlds would be truly staggering.