(11 of 17)

In Yunnan province, Liang Weifeng got a state bank loan of $965 to buy a two-wheel tractor; he earned enough hauling firewood, bricks and grain for his neighbors to pay off the loan in eight months. Liang now clears about $1,660 a year from his business, which his wife Su Yongchang supplements with about $230 earned by raising rice and vegetables on a plot of a bit less than an acre. Su claims to know little about Deng or politics: "I only know that the policies now are good, so that we can get rich."

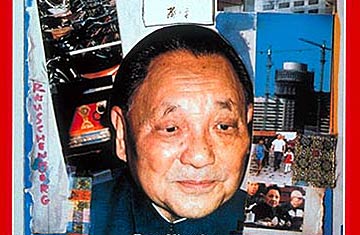

Consciously or unconsciously, she is echoing a line of argument often voiced by Deng and his supporters. In the name of economic growth, they are quite deliberately fostering a growing inequality of incomes. Says Deng: "Some people will become prosperous first, and then others will become prosperous later." But since honoring and emulating the rich goes against the Marxist grain, Deng and his allies have developed an elaborate justification: there is nothing wrong with wealth so long as it is earned by one's own labor rather than by the exploitation of the labor of others, which Marx condemned. Or, in the words of a onetime slogan that Writer Orville Schell turned into the title of a book, "To Get Rich Is Glorious."

Such heretical thoughts are heard often enough these days to raise an insistent question: Can the system they are erecting still be called Marxist? It is far more than a matter of semantics. Marxism has demonstrated dramatic power to shake the world, and thus any debate as to what it does and does not consist of is of paramount importance.

The question, however, is far from easy to answer. Since Marx died in 1883, his admirers have written innumerable explanations of his work. They have frequently, and often fanatically, denounced one another as revisionists or worse. But Bertell Ollman, a professor at New York University and an avowed Marxist, observes that "Marx had very little to say of a concrete nature about socialism," the transitional society that would follow the revolution Marx preached. (In strict Marxist terminology, "Communism" is the ideal stateless society to be reached as an ultimate goal.) The only way to get a definitive opinion on the features of Marxist socialism, says Harry Harding, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, would be "to bring Karl back to speak for himself."

The version of Marxist thought that eventually won out, because it achieved power, was Marxism-Leninism, after V.I. Lenin, the leader of the Bolshevik Revolution. According to Lenin, Marx's call for a "dictatorship of the proletariat" meant that a tightly organized Communist Party was to be the exclusive dominating force in transforming society. Among the millions attracted by this prescription were two young Chinese, named Mao Tse-tung and Deng Xiaoping, who saw in it a way to change their country from a weak, backward state pushed around by foreign powers to a mighty modern nation. Deng has remained a model Leninist in the sense of countenancing no challenge to the Communist Party's role in leading society, even when portions of the party balk at carrying out his reforms.