(10 of 17)

In foreign policy, the motto under Deng seems to be: try to get along with everyone so that the nation's energies can be concentrated on economic development. China has cautiously resumed trade and cultural exchanges with the Soviet Union. Peking has spared little effort in trying to convince the non-Communist nations of Asia that it intends to be a peaceful neighbor. It stopped aid to Communist rebels in Thailand in the late 1970s, and today disavows any idea of helping those in Malaysia, Indonesia or the Philippines. The only guerrillas China is aiding today are those battling the Soviet army in Afghanistan and the Soviet-backed Vietnamese occupiers of Kampuchea.

The most striking achievement of this don't-rock-any-boats policy is a deal signed with Britain a year ago under which Peking in 1997 will assume sovereignty over Hong Kong on a pledge to maintain Hong Kong's wide-open, laissez-faire capitalist system for at least 50 years after that. Peking is now touting an even more lenient version of this "one nation, two systems" approach as a model for a reunification deal with Taiwan, which it once threatened to take by force. Peking proposes to let Taiwan retain not only a capitalist economy but independent armed forces. Taiwan so far is not buying. Eager for more trade and investment, Deng is trying to make China a partner in the non-Communist world economic system. In 1986 Peking expects to apply for full membership in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, the 90-nation organization that monitors world-trade rules.

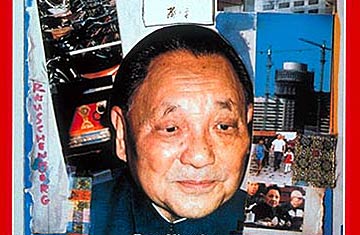

As striking as the transformation of China into a power dedicated to stability has been, it is economic rather than foreign policy that will determine Deng's place in history. He has staked everything on the success of his economic reforms, arguing that whatever their theoretical justification or lack of it, they will work. And so far they generally do.

True, China is still a poor country by any measure. Deng's goal is to lift per capita income to $800 by the year 2000. That would compare with a 1980 level of $300 and would be sufficient to admit China to the ranks of middle-income countries. But as recently as 1982, average incomes in China were about equal to those in poverty-ridden Haiti. Travelers in Sichuan province note that many peasants still use wheelbarrows with wooden wheels and iron rims and till the fields with wooden plows--this in a country where museums display iron plows from the Han dynasty 2,000 years ago.

But life is getting better, fast, for many Chinese. Industrial production has leaped along with food output. Early in 1985 it was increasing at an annual rate of 23%, a pace Deng and his planners judged too rapid. They ordered a slowdown to avoid shortages and worsening inflation. In Mao's days, Chinese consumers dreamed of buying the "three bigs": a bicycle, a wristwatch and a sewing machine. Now the three bigs are a refrigerator, a washing machine and a TV set. "Imagine," says a Western diplomat. "Some people living in the heart of Guizhou province now see the evening news, with film from Beirut and New York. Three years ago, they did not know anybody lived on the other side of the nearest hill."