Roy Wilkins

(6 of 10)

The Ex-Heroes. In the rush of the revolution, Negro heroes fall fast. Less than a year ago, with the help of 16,000 federal troops sent in by President Kennedy, Negro James Meredith enrolled at the University of Mississippi. He graduated last week—but as a result of several statements he has made, he is now scorned by many Negroes as being too "moderate." James Hood, first male Negro ever to be enrolled at the University of Alabama, got along pretty well for a while—to the point that he started saying critical things about Negroes in public. As a result, he was so hounded by other Negroes that to get back on the right side of his own people he turned around and denounced university officials. Two.weeks ago, facing expulsion, he withdrew from Alabama. *

Similarly, the revolution sometimes imposes impossible demands on Negro leaders who try to be truthful. Says a Negro member of the Illinois state legislature: "Now, just by making a sober, honest judgment on how civil rights should be won, you can be called an Uncle Tom by anyone who disagrees. What does this do to Negro leadership? It demolishes it." And Massachusetts' Attorney General Edward Brooke, the highest elected Negro official in the nation, has made many Negro enemies because, even while going all out for civil rights, he argues that the Negro, too, has obligations to uphold. Says Brooke about Boston's Columbia Point Housing Project, which has many Negro tenants: "There's writing all over the walls, and children defecate right in the halls when there's a bathroom a few feet away. You can't just offer people equal opportunities; you have to show them what to do with those opportunities."

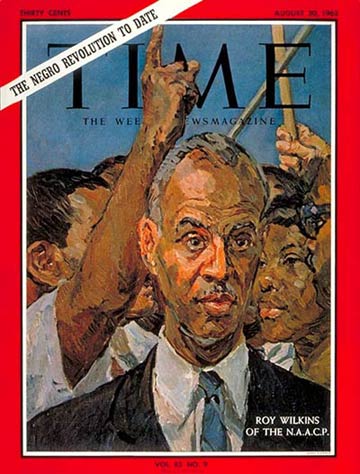

A Variety of Weapons. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People as headed by Roy Wilkins (he succeeded White in 1955) has also suffered under the pressures of the Negro revolution. But it has survived them and maintained its leadership. One reason is that Wilkins himself is a firm believer in the idea that the Negro should use every possible means to achieve his rights. If persuasion will serve, that is fine. But if violence is required, Wilkins accepts it. Said he in a recent speech: "The Negro citizen has come to the point where he is not afraid of violence. He no longer shrinks back. He will assert himself, and if violence comes, so be it."

What Wilkins really believes in is variety in attack. When street demonstrations seem likely to be effective, Wilkins is wholeheartedly for them. "But," he insists, "demonstrations are like prepping a patient for surgery.

They often serve to get a community ready, and then we can move in with our other approaches. CORE people are good commandos. But Southern whites who regard the N.A.A.C.P. as the most dangerous enemy are correct. We have stuck to our knitting and used all our weapons." In that same sense,