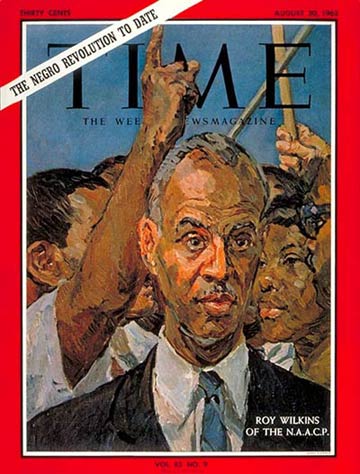

Roy Wilkins

If there is no struggle, there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom, and yet deprecate agitation, are men who want crops without plowing up the ground. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters.

—Abolitionist Negro Frederick Douglass, 1857

In 1963, that awful roar is heard as never before.

"My basic strength is those 300,000 lower-class guys who are ready to mob, rob, steal and kill," boasts Cecil Moore, 48, head of the Philadelphia branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Says Mel Ladson, 26, a Miami leader in the Congress of Racial Equality: "I want to be able to go in that restaurant and eat, and it doesn't mean a damn to me if ,the owner's guts are boiling with resentment. I want to nonviolently beat the hell out of him."

Predicts Dr. Gardner Taylor, 45, Negro pastor of Brooklyn's Concord Baptist Church: "The streets are going to run red with blood."

Cries the Rev. James Bevel, a Mississippi official of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference: "Some punk who calls himself the President has the audacity to tell people to go slow. I'm not prepared to be humiliated by white trash the rest of my life, including Mr. Kennedy."

These are voices—some voices—of the Negro revolution. That revolution, dramatically symbolized in this week's massed march in Washington, has burst out of the South to engulf the North. It has made it impossible for almost any Negro to stay aloof, except at the cost of ostracism by other Negroes as an "Uncle Tom." It has seared the white conscience—even while, in some of its excesses, it has created white bitterness where little or none existed before. And right up to the President of the U.S., it has forced white politicians who have long cashed in on their lip service to "civil rights" to put up or shut up.

The Welcome Pressure. Like every revolution, the Negro revolution is formless. It is, as ex-Slave Douglass said it must be, an oceanic tide of many waters. The voices of hatred are in the minority—so far. But they often drown out softer, equally determined and far more effective Negro voices.

Obviously, no Negro can speak for all. No organization can represent all Negro aspirations. But in the late summer of 1963, as the revolution intensifies, if there is one Negro who can lay claim to the position of spokesman and worker for a Negro consensus, it is a slender, stoop-shouldered, sickly, dedicated, rebellious man named Roy Wilkins.

Wilkins, 62, is executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the oldest (founded in 1909), biggest (400,000 members, and growing at the rate of 5% a year), and most potent of U.S. civil rights organizations. Wilkins himself is a professional in the business of protest. As a reporter and managing editor of Kansas City's crusading Negro weekly, the Call, for eight years, and as a fulltime N.A.A.C.P. worker for 32, he was a racial rebel in the days when the white man's answer was not just a paddy wagon but, all too often, a lynch mob's rope.

Among many young, highly militant Negroes, it has become fashionable to denounce the N.A.A.C.P. as oldfashioned. Wilkins is keenly aware of the