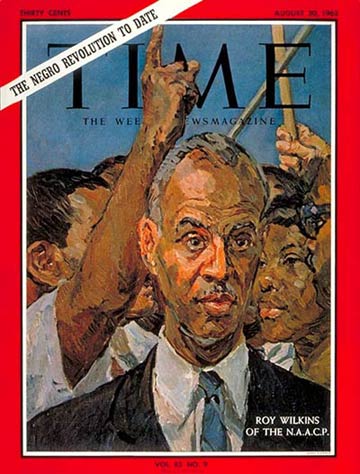

Roy Wilkins

(4 of 10)

In the antilynch battle, the most powerful weapon of the N.A.A.C.P. was publicity. Wilkins' boss, Walter White, was a superb propagandist. Actually one sixty-fourth Negro in family-tree terms, White insisted upon classifying himself as a Negro. He was blond and blue-eyed, and one of his favorite tactics was to go out to investigate a lynching, pass himself off as a white newsman, win the confidence of local law officials—and return to write a brutally detailed report.

The N.A.A.C.P. never did achieve its main aim, that of a federal antilynch law. But it did impress itself enough on the white conscience to end lynching.

Slowly, tortuously, the lynch rate fell from 64 in 1921 to 28 in 1933 to five in 1940 to, for the first time, none in 1952. To be sure, white hoodlums still love to lob bombs at the homes of Negro leaders, but the last real lynch killing that the U.S. has known was that of Mississippi Negro Mack Charles Parker in 1959. Says the N.A.A.C.P.'s Wilkins: "We have completely changed the thinking of the country on lynching. At one time it was defended in the Senate, and even in the pulpit. There is no comparison now with the fear we once knew."

"Paper Decrees." Once the struggle against lynch law was won, the N.A.A.C.P. could give top priority to another drive—against segregated education. By deliberate decision, the organization made that assault not so much in the press, or on the streets, or in the lobbies of Congress, but in the courts. N.A.A.C.P. Special Counsel Thurgood Marshall pleaded the cause of school integration before the Supreme Court, was upheld in the historic decision of 1954—and in the minds of many Negroes at the time, that decision opened the way to real racial equality in the U.S.

This expectation fell far, and tragically, short of fulfillment. In both South and North, public officials found all sorts of ways to delay, avoid or simply ignore implementation of the Supreme Court's order. Dashed to the ground, Negro hopes arose once more in 1957, when President Eisenhower ordered federal troops into Little Rock to enforce token high school integration.

But even after Little Rock, progress seemed agonizingly slow. And in their disappointment, a multitude of Negroes began blaming the N.A.A.C.P. for its reliance upon the slow, stolid processes of the courts. Declared Negro Journalist Louis Lomax, 41: "The Negro masses are angry and restless, tired of prolonged legal battles that end in paper decrees. The organizations that understand this unrest and rise to lead it will survive; those that do not will perish." Asked if he thought his national leaders were asleep at the switch, Jersey City N.A.A.C.P. President Raymond Brown snapped: "Hell, they don't even know where the switch is." Some Negroes furiously turned to such Negro nationalist groups as the Black Muslims, whose New York leader, Malcolm X, tells whites: "The N.A.A.C.P. is a white man's concept of a black man's organization. Don't let any of those black integrationists fool you. What