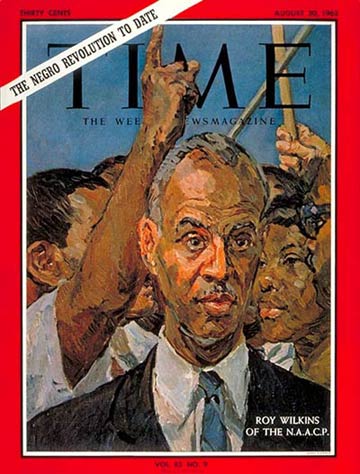

Roy Wilkins

(3 of 10)

The N.A.A.C.P.'s lifetime is covered almost exactly by that of Roy Wilkins. The grandson of a Mississippi slave, he was born in St. Louis in 1901. His mother died of tuberculosis, and because his father was not able to keep the family together, Roy was reared in St. Paul by an aunt and an uncle. In a poor but racially mixed neighborhood, Roy's best friends included three Swedish kids named Hendrickson. To help pay for his sociology studies at the University of Minnesota, Wilkins worked as a redcap in St. Paul's Union Station and as a dining car waiter on the Northern Pacific, also labored on the cleanup squad at the South St. Paul stockyards in a room where congealed cattle blood was sometimes 18 inches deep.

After graduation from college, Wilkins landed a job on the Call in Kansas City—and it was there that he first really learned what it can mean to be a Negro in the U.S. "Kansas City ate my heart out," he recalls. "It was a Jim Crow town through and through. There were two school systems, bad housing, police brutality, bombings in Negro neighborhoods. Police were arresting white and Negro high school kids just for being together. The legitimate theater saved half of the last row in the top balcony for Negroes. If the show was bad, they gave us two rows."

The Rope's End. As one expression of his protest, Wilkins intensified his N.A.A.C.P. activities. But when the organization offered him a job on its magazine, the Crisis, he turned it down, fired off a frankly critical letter to N.A.A.C.P. headquarters in New York.

The letter so impressed organization officers that they called Wilkins in for an interview and wound up hiring him as an aide to Executive Secretary Walter White.

At that time, the N.A.A.C.P.'s most massive efforts were directed against lynchings—and it is difficult for Americans today to realize just what terror that word held for Negroes. For the 30 years ending in 1918, the N.A.A.C.P. lists 3,224 cases in which people were hanged, burned or otherwise murdered by white mobs. No Negro could feel really safe—for reasons perhaps best described in the well-authenticated report of one famed lynching: "A mob near Valdosta, Ga., frustrated at not finding the man they sought for murdering a plantation owner, lynched three innocent Negroes instead; the pregnant wife of one wailed at her husband's death so loudly that the mob seized her and burned her alive, too." Says Roy Wilkins of the priority given by the N.A.A.C.P. to its antilynch efforts: "We had to stop lynching because they were killing us. We had to provide physical security."

Wilkins himself suffered his first (and one of his few) arrests as a picket in Washington in 1934 after Franklin