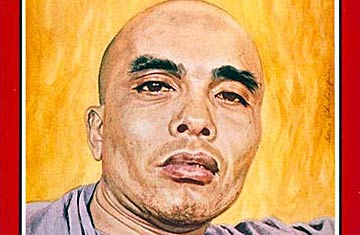

Thich Tri Quang

(5 of 9)

Helping Ho. Tri Quang is his adopted name, and it means "brilliant mind." He was born Pham Bong on Dec. 31, 1923, in Diem Dien, a village in central Viet Nam now under Hanoi's rule. One of three sons of a well-to-do farmer, he was sent at the age of 13 to the Bao Quoc pagoda in Hué to train for monkhood. Wild and fond of practical jokes at first, he was expelled, then given a second chance. He matured into a student with a photographic memory and a searching intellect. His teacher at Bao Quoc, Thich Tri Do, who now heads the tame Buddhist church of North Viet Nam, guided the impressionable novice into the winds of nation alism sweeping the then French colony.

In 1946 the young monk, possessing nothing but his begging bowl, his robe and a pair of rubber sandals, went with Tri Do to Hanoi. There he caught sight of Ho Chi Minh and was swept by the fever for freedom from the French. In the years of war against Paris, the French suspected, probably rightly, that the lithe bonze with the burning eyes was helping Ho's Viet Minh front. They once jailed him for ten days on suspicion that he was a Communist, but they could not prove it—nor has anyone since, despite the taint of suspicion that still lingers in many quarters. More probably, like many a loyal South Vietnamese of that day, Tri Quang aided Ho's campaign not for love of Communism but for hatred of colonialism.

"The Perfect Conspirator." When the French were thrown out and President Ngo Dinh Diem took over in 1955, Tri Quang, in common with many of his brother monks, was hardly over joyed. For 80 years under the French, Catholicism had been nurtured at the expense of Buddhism, and a Catholic church occupied the choice site in every town. Catholic schools provided education that the Buddhists could not afford to match, and Catholic merchants and civil servants, thus equipped, inevitably prospered. To Tri Quang, the Catholic Diem was merely an extension of the worst ills of French rule. In the monk's mind, Buddhism and nationalism were inextricably mixed and Diem was a blasphemy on Viet Nam's true destiny. Coolly and quietly, Tri Quang set out to destroy him.

It took him seven years—years in which ostensibly he lived the life of an ordinary, if exceptionally austere, bonze. Abstaining from meat, cigarettes and liquor, he lived in a cramped cell in Hué's Tu Dam pagoda, rising with the "first sun on a man's hand," spending a third of his waking day in prayer, a third in activity, a third in contemplation of his mistakes. Twice he served as president of the Hué Buddhist Association, his stints interrupted by a total absence from public view from 1959 to 1961. His life has been filled with such disappearances, but then, even his appearances are deceiving.