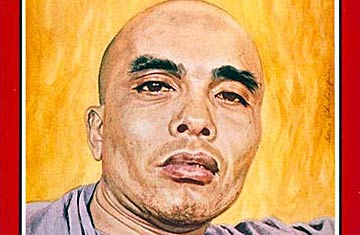

Thich Tri Quang

(4 of 9)

Riffling Reports. For Tri Quang, it had been a satisfying week's work. Receiving and dispatching emissaries in Room 12-F in the Duy Tan maternity clinic, his customary quarters in Saigon, riffling through reports with the practiced eye of a corporation executive, he took time out at week's end to talk to TIME Correspondents Frank McCulloch and James Wilde, and made some of the most intriguing statements of his career (see box opposite). For a man famed for his elusiveness and enigmatism, his answers seemed remarkably reasonable—and encouraging to the U.S. He condemned Communism, not only welcomed the continued assistance of U.S. troops in Viet Nam but suggested that his government might enhance their value and use. He insisted that the Buddhists do not want predominance in the elections or the assembly; that was Diem's mistake, and the Buddhists do not intend to repeat it.

Whether Tri Quang is as reasonable as he sounds is, of course, debatable on the basis of his past history. He has said several things on several sides of many subjects, and he does not scruple to stretch the truth. Still, he would not be the first politician to discover that imminent power can alter and enlarge a range of responsibility. What was transparently clear was Tri Quang's goal of backstage power for himself. He covets no public post, disdains such titles as president and premier as Western innovations imposed on Viet Nam's ancient traditions. But even if the Buddhists do not gain a predominant grip on the elected assembly, he knows well that the next civilian government will be beholden to him and more vulnerable to Buddhist pressure tactics than any military government.

Real Danger. All the while that Tri Quang has been battering the central government, the war has been carried on, with effectiveness where the enemy can be found but inevitably at a reduced rate because of the Vietnamese army's involvement in the crisis. The real danger so far has been not so much a slackening of the war against the Viet Cong as the ever present threat that Saigon's internecine bickering might explode into a full-fledged civil war that would engulf the Americans in Viet Nam. The possibility of such violence seems to disturb Tri Quang no more than did the task of sending his stone-throwing gangs of town toughs and slum children into the streets to riot.

Encouraging twelve-year-old boys to mix Molotov cocktails hardly seems appropriate for a priest of the Buddha, who preached reverence for life and recommended to monks an eightfold path to nirvana. Nor is overthrowing governments exactly the middle road along which Gautama enjoined his disciples to escape from worldly desires. But then Thich Tri Quang is hardly a copybook example of the Sarvastivadin's Book of Discipline for Buddhist monks, whose tenth admonition forbids a monk "to persist in trying to cause divisions in a community that lives in harmony, and in emphasizing those points that are calculated to cause division." Part of the explanation is that Buddhism in Viet Nam is largely Mahayana, a branch of Buddha's teachings emphasizing social concern for others as well as the withdrawal of self. Even more, Thich Tri Quang is not only a Buddhist bonze but peculiarly a child of his times in Viet Nam.