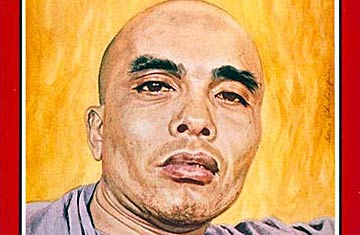

Thich Tri Quang

South Viet Nam

(see cover)

The stench of cordite and the sour-sweet smell of tear gas—the incense of South Viet Nam's political crisis—was missing in Saigon last week for the first time in more than a month. The frail, elegant hands of the Buddhist bonze who had ignited the trouble gestured—and the mobs went home, the air cleared. The crisis itself had not ended, but its course had been changed and channeled, sometimes subtly, sometimes imperiously, by one of South Viet Nam's most extraordinary men. As a result of the power and discipline he displayed in last week's events, one thing became eminently clear: South Viet Nam's political future for some time to come will be very much influenced by a servant of Buddha, the Venerable Tri Quang.

Lean, well-muscled, with a sensual electricity, in every gesture and blazing eyes that can mesmerize a mob, Thich Tri Quang, 42, has long been South Viet Nam's mysterious High Priest of Disorder. (Thich, pronounced tick, is a title meaning "venerable"; Tri Quang is pronounced tree kwong.) Wily and ruthless, Delphic and adept, he is the best of breed of a new kind of back room bonze. In the murky world of Oriental mysticism and Saigon's immemorial intrigue, these robed and shaven men have emerged as the new Machiavellis of the Vietnamese political scene. Tri Quang is unquestionably their prince.

Like the legendary crane of Chinese mythology, Tri Quang throughout his career has largely managed to shroud himself from mortal view, appearing only now and then as an exclamation point to specific events. A master of means whose ends are obscure, he is, in maddening succession, devious, enigmatic, contradictory and blandly opaque. The only thing self-evident about him is his burning desire for power, his urgent ambition not only for himself but, presumably, for his people —the Buddhists of South Viet Nam.

Saint or Seer? To his mission, Tri Quang brings an intelligence and a toughness that have not been seen in a South Vietnamese leader since Ngo Dinh Diem, whose downfall the ascetic bonze triggered in 1963. Since then he has added the scalps of three more governments. Last week he scored another triumph, this time over the Directory of generals headed by Premier Nguyen Cao Ky. It was no small feat, since the generals comprise the combined armed might of South Viet Nam, but Tri Quang is armed with his own powerful weapons: an unerring instinct for politics, a perfect sense of timing and a control over his followers that borders on the charismatic.

Naturally, he inspires wildly conflicting responses. To some seasoned Saigon observers, he is by far "the most dangerous man in South Viet Nam." To a young American girl who works near him in Saigon's Buddhist Institute for the Propagation of the Faith, Vien Hoa Dao, he seems "affable, fallible and lovable." U.S. officials who must deal with him are both awed and appalled. Former U.S. Ambassador Maxwell Taylor in exasperation once called him "the Makarios of Southeast Asia"—though he is far more retiring and ascetic than Makarios. One of his Buddhist rivals insists that he is an anarchist. The Catholics are certain that he is a Communist. He has been variously described as a demagogue, a saint, a puppetmaster, a seer and "the mad monk."