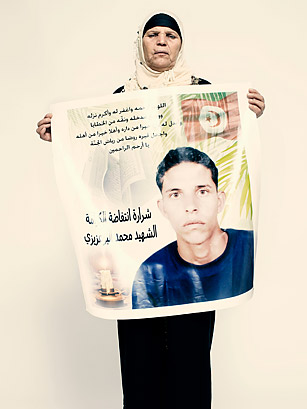

"Mohamed suffered a lot. He worked hard. But when he set fire to himself, it wasn't about his scales being confiscated. It was about his dignity."

—Mannoubia Bouazizi, Tunisia

(8 of 8)

So America's great 21st century contribution to fomenting freedom abroad was not imposing it militarily but enabling it technologically, as an epiphenomenon of globalization. And for a second act, globalization returned the favor, turning democratic uprisings in developing countries into inspirational exports for the rich world. "We were on the receiving side," Egyptian presidential candidate Amr Moussa told me, "and now we are on the sending side. We have contributed to this global movement for change. There's a new spirit. The grassroots are revolting — young people on Wall Street and young people in Europe."

Ever since modern republican democracy was invented, astonishing protests and uprisings have spiked and spread once every half-century or so: the revolutions in America and France and Haiti; the revolutions of 1848; the revolutions of the 1910s (Russia, Germany, Ireland, Turkey, Egypt, Mexico); the postwar wave of worldwide revolt (the movements toward decolonization, Cuba, Hungary, American civil rights, countercultural militancy in America and Europe). It happens almost like clockwork, yet each time people are freshly shocked and bedoozled. So here we are again. History isn't a very precise guide to how long it might persist this time. In 1848 the revolutionary moment was explosive but lasted only a year, extinguished by both dictatorial and democratic counterrevolutions. The revolutionary dream hatched around 1960, however, was still powerfully contagious a decade later.

The nonleader leaders of Occupy are using the winter to build an organization and enlist new protesters for the next phase. They have shifted the national conversation. As Politico recently reported, the Nexis news-media database now registers almost 500 mentions of "inequality" each week; the week before Occupy Wall Street started, there were only 91. But what would count, a few years hence, as success? According to gung-ho Adbusters editors Kalle Lasn and Micah White, it's already "the greatest social-justice movement to emerge in the United States since the civil rights era." Yet it took a decade to get from the Montgomery bus boycott to the federal civil rights acts, which were just the end of the beginning.

The wisest Occupiers understand that these are very early days. But as long as government in Washington — like government in Europe — remains paralyzed, I don't see the Occupiers and Indignados giving up or losing traction or protest ceasing to be the defining political mode. After all, the Tea Party protests subsided only after Tea Partyers achieved real power in 2010 by becoming the tail wagging the Republican Party dog. When radical populist movements achieve big-time momentum and attention, they don't tend to stand down until they get some satisfaction.

Protesters are ready to rumble in Egypt and Tunisia if democracy and freedom seem too compromised. Emboldened protesters may yet sweep away regimes in places like Jordan and Yemen. In Libya, a bloody revolution, assisted by NATO, brought down the 42-year-old regime of Colonel Muammar Gaddafi. The protorevolution is still under way in Syria, where thousands of protesters have been killed.

And in Russia, the recipe for surprising protest circa 2011 — pseudodemocratic-regime overreach, high Internet use, robust new media and suddenly galvanized middle-class youth — is being baked and served. On Dec. 5, after Putin's party, United Russia, did badly in parliamentary elections despite apparent ballot-box stuffing, more than 5,000 Muscovites gathered to chant, "Russia without Putin!" and called for his arrest. It was the largest Russian antiregime protest of the 21st century — and just as in Tunis and Madrid and New York City, nobody saw it coming.

These Russian protesters are a new breed, not just nostalgic old communist grandmas or bullyboy nationalists but yuppies, students, the best and brightest. "So this is what they look like," said Oleg Orlov, the 58-year-old head of Russia's main human-rights organization, as he scanned the square at Chistye Prudy the night of Dec. 5. "I've never seen them at rallies before, at least not in such enormous numbers. It's incredible."

Alexei Navalny, the blogger who coined a new United Russia moniker — "the party of crooks and thieves" — addressed the protesters. "They can laugh and call us microbloggers. They can call us the hamsters of the Internet. Fine. I am an Internet hamster. But I know they are afraid of us." The protesters cheered. And then 300 of them and Navalny were arrested. The next night in Triumfalnaya Square, protesters returned, and 600 were arrested. A Putin spokesman declared that "unsanctioned demonstrations must be stopped."

On Dec. 10, five days after the first protest, tens of thousands gathered in Moscow in the largest demonstration since just after the fall of communism. There were simultaneous protests in dozens of other cities all over Russia. A letter written by Navalny from his Moscow jail cell was read to the crowd. "It's impossible to beat and arrest hundreds of thousands, millions. We are not cattle or slaves. We have voices and votes, and we have the power to uphold them." An even bigger protest is scheduled for Dec. 24.

They are protesting corruption and the lack of real freedom and true democracy. Because Russia, like most of the world, has not quite totally arrived at the end of history.

— With reporting by Rania Abouzeid / Tunis; Abigail Hauslohner / Cairo; Simon Shuster / Moscow; Lisa Abend / Madrid; Joanna Kakissis / Athens; Nilanjana Bhowmick and Jyoti Thottam / New Delhi; Nate Rawlings and Ishaan Tharoor / New York; Jason Motlagh / Oakland; and Tim Padgett / Mexico City