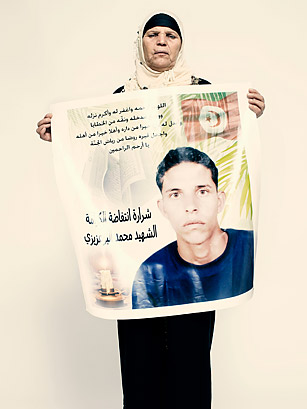

"Mohamed suffered a lot. He worked hard. But when he set fire to himself, it wasn't about his scales being confiscated. It was about his dignity."

—Mannoubia Bouazizi, Tunisia

(5 of 8)

In early August, after police in London shot and killed a young black man they were arresting, riots broke out all over England. Naturally, the rioters' instantly resorting to violence attracted little sympathy. Yet a new, three-month study by the Guardian and the London School of Economics concluded that these rioters were also protesters, motivated by anger about poverty, unemployment and inequality as well as overaggressive policing.

Back in Madrid, the protesters recognized the diminishing returns of this protest phase and started to decamp. By July, Gálvez says, they heard that Occupy Wall Street was going to happen. Online, the Indignados started explaining to the Americans how it's done.

Since 1989 the earnest, zany little bimonthly Adbusters — "an ad-free international magazine for activists fighting to change the way information flows and meaning is produced in our society" — had been preaching to its choir. In July the editors ran a full-page photo-illustration of a barefoot ballerina posed atop Wall Street's Charging Bull statue — in the background were gas-masked insurgents in a tear-gas fog — along with four lines of copy: "What is our one demand? #occupywallstreet September 17th. Bring tent." Adbusters also sent out an e-mail — "America needs its own Tahrir" — and on Independence Day urged on its smallish cadre of Twitter followers: "Dear Americans, this July 4th dream of insurrection against corporate rule."

If you tweet it, they will come.

At the end of July, in an office in New York's financial district, the proto-Occupiers met with some veterans of the protests in Spain, Greece and North Africa. To figure out what "Occupy Wall Street" might mean, they reconvened two days later at a come-one-come-all meeting — outdoors, for hours, in a park near that charging bronze bull, amid the thousands of unwitting passersby on an ordinary Wall Street workday.

David Graeber, 50, a prominent anthropology scholar and soft-spoken pro-anarchism activist, showed up. Some standard leftists were pushing for a standard rally making a standard demand — no cutbacks in government social spending. Slowly but surely, Graeber and a pal, 32-year-old Greek émigré artist Georgia Sagri, nudged the group to a fresh vision: a long-term encampment in a public space, an improvised democratic protest village without preappointed leaders, committed to a general critique — the U.S. economy is broken, politics is corrupted by big money — but with no immediate call for specific legislative or executive action. It was also Graeber, a lifelong hater of corporate smoke and mirrors, who coined the movement's ingenious slogan, "We are the 99%."

Until late September, 99% of New Yorkers had never heard of Zuccotti Park, a privately owned public plaza tucked between the Federal Reserve Bank and the World Trade Center site. On the last Saturday of the summer — sunny, mid-60s, perfect — a couple thousand people showed up, a hundred slept overnight, and the occupation was on. It seemed as though the world would little note nor long remember it. On the third day, the first arrests — of protesters wearing Guy Fawkes masks in violation of an antique New York anti-insurrection statute — got scant attention.

It was through my Twitter feed that I started noticing that something was going on in my city. The following weekend, I watched the YouTube video of a New York police deputy inspector casually pepper-spraying some random female protesters. A few days later, my 24-year-old nephew, Daniel Thorson, e-mailed from his small town in western New York: he was coming down to occupy Wall Street, and could he stay with us in Brooklyn?

At Hobart and William Smith Colleges, Daniel was a philosophy major, lived in a frat house, volunteered for the Obama campaign and co-founded his campus's chapter of the nonpartisan Americans for Informed Democracy. Since graduating, he's held various minimum-wage and unpaid jobs and has grown deeply disappointed by how little the Obama Administration has been able to accomplish. In September he was stunned by the breadth and depth of the chatter on his Twitter and Facebook feeds about Occupy Wall Street and decided he wanted to be part of it.

As soon as he arrived at Zuccotti Park, he went to the information desk. "It was staffed by someone who wasn't very articulate," he told me, "who wasn't the face of what I thought this should be." He offered to pitch in and thus became a member of the information working group. He helped guide the general assemblies, OWS's daily town meetings, reveling in the process of debating and deciding. To me it sounded like being a facilitator at a corporate management retreat — except outdoors, with everyone voting by means of kooky hand signals and making sure the anarchists are heard. Even if I were a 24-year-old idealist, I told Daniel, I would have zero patience for the process. He'd get annoyed from time to time by "craziness, by a sense of entitlement, anger, resentment," he said. "But there are jerks in every organization, no matter how 'pure' the organization."

In a new book from TIME, What Is Occupy? Inside the Global Movement, our journalists explore the roots and meaning of the uprising over economic justice. To buy a copy as an e-book or a paperback, go to time.com/whatisoccupy.