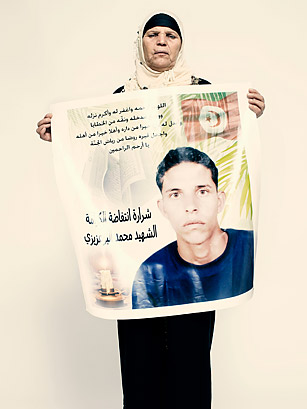

"Mohamed suffered a lot. He worked hard. But when he set fire to himself, it wasn't about his scales being confiscated. It was about his dignity."

—Mannoubia Bouazizi, Tunisia

(6 of 8)

After my wife and I kicked him out of our house — three weeks seemed like a fulfillment of avuncular duty — Daniel slept at the park most nights. At around 1 a.m. on the final night of the encampment in November, he was at a friend's apartment when he got a text message — police en route, eviction imminent. He rushed downtown, but new police barricades kept him and other protesters a block away up Broadway. They were ordered to scram, most of them refused, the pepper spray came out, and the police announced they'd be arrested if they didn't leave the sidewalk. Daniel spent 38 hours in custody, charged with resisting arrest, disorderly conduct and obstructing governmental administration.

I found out about his arrest and release — via e-mail and a Facebook status update — in Cairo, as I walked through Tahrir Square during the first of the recent, huge anti-junta protests. My interpreter, a young Jordanian immigrant to Egypt, was excited about Occupy Wall Street. "It's going viral," he said. "I know it's now like in 80 countries."

And in cities all over the U.S., of course, with all kinds of people protesting. Among the thousands occupying Oakland was Arthur Chen, 60, a family-practice physician. For him, "the expression of outrage was very on target with our current economic crisis and the way it's impacting the 99%," especially his low-income and uninsured patients. During his first day occupying Oakland, Chen remembers, "one of the announcers said, 'You're going to hear some things that you may totally disagree with.' I chuckled, and then I thought, 'This generation really is about inclusiveness and transparency.' It was very moving."

In Cairo, meanwhile, there was Ahmed Harara, 31, a dentist who lost sight in both eyes to rubber bullets in Tahrir on two separate occasions — in January and November, when he returned for the anti-junta protests. What was the most memorable day of his whole annus mirabilis cum horribilis? "Actually," he said, "there are two days — the 28th of January here in Egypt and the day when Americans occupied Wall Street. Because here in Egypt, we raised the slogan of social justice, and I see that Americans need it and did that too."

The Beginning of History

Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,

But to be young was very heaven!—Oh!

times,

In which the meagre, stale, forbidding

ways

Of custom, law, and statute, took at once

The attraction of a country in romance!

—William Wordsworth, "The French Revolution as It Appeared to Enthusiasts at Its Commencement"

Aftermaths are never as splendid as uprisings. Solidarity has a short half-life. Democracy is messy and hard, and votes may not go your way. Freedom doesn't appear all at once. Just off Tahrir, when a couple of us were taking pictures of a graffiti about a blogger the army had imprisoned, a scowling secret policeman appeared and waved us away. We were unwanted tourists at the revolution.

Globalization and going viral have been the catchphrases of the networked 21st century. But until now the former has mainly referred to a fluid worldwide economy managed by important people, and the latter has mostly meant cute-animal videos and songs by nobodies. This year, do-it-yourself democratic politics became globalized, and real live protest went massively viral. But as they've rejuvenated and enlarged the idea of democracy, the protesters, and the rest of us, are discovering that democracy is difficult and sometimes a little scary. Because deciding what you don't want is a lot easier than deciding and implementing what you do want, and once everybody has a say, everybody has a say. No one knows how the revolutions will play out: A bumpy road to stable democracy, as in America two centuries ago? Radicals' taking over, as in France just after the bliss and very heaven? Or quick counterrevolution, as in France 60 years later? The mostly liberal, secular young people who made the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt last winter have been subordinated, if not sidelined, by better-disciplined political organizations. And they all agree it's partly their own fault, a function of naiveté about the realities of democratic politics.

"The only good thing Mubarak did," activist Mahmoud Adel Elhetta told me, "was unite us." Mahmoud Salem, 30, who blogs and tweets under the name Sandmonkey — and who has an American B.A. and M.B.A. and works in business development for clients like Coca-Cola — told me he "had the hubris of youth. It was utopia that immediately descended into chaos." He lost his election for a parliamentary seat representing a wealthy Cairo district two weeks ago. "We failed," says el-Ghazali Harb, the surgeon-revolutionary. "What made the revolution happen is the youth. We handed it back to the seniors. We didn't trust ourselves."