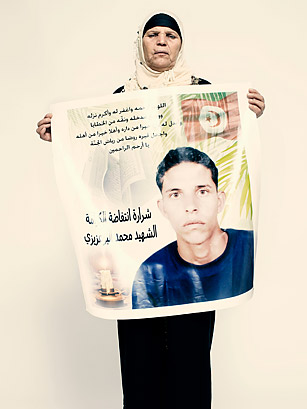

"Mohamed suffered a lot. He worked hard. But when he set fire to himself, it wasn't about his scales being confiscated. It was about his dignity."

—Mannoubia Bouazizi, Tunisia

(2 of 8)

It's remarkable how much the protest vanguards share. Everywhere they are disproportionately young, middle class and educated. Almost all the protests this year began as independent affairs, without much encouragement from or endorsement by existing political parties or opposition bigwigs. All over the world, the protesters of 2011 share a belief that their countries' political systems and economies have grown dysfunctional and corrupt — sham democracies rigged to favor the rich and powerful and prevent significant change. They are fervent small-d democrats. Two decades after the final failure and abandonment of communism, they believe they're experiencing the failure of hell-bent megascaled crony hypercapitalism and pine for some third way, a new social contract.

During the bubble years, perhaps, there was enough money trickling down to keep them happyish, but now the unending financial crisis and economic stagnation make them feel like suckers. This year, instead of plugging in the headphones, entering an Internet-induced fugue state and quietly giving in to hopelessness, they used the Internet to find one another and take to the streets to insist on fairness and (in the Arab world) freedom.

All over the world they are criticized by old-schoolers for lacking prefab ideological consistency, which the protesters in turn see as a feature rather than a bug. Miral Brinjy, a 27-year-old blogger and TV-news producer who grew up in Saudi Arabia and arrived in Tahrir Square on the first day of protests 11 months ago, doesn't presume to have a precise picture of the new Egyptian government and society she envisions, but as she told me in Cairo last month, "I know what I don't want."

In each place, discontent that had been simmering for years got turned up to a boil. There were foreshadowings. In the U.S., the Obama campaign was in part a feel-good protest movement that galvanized young people, and then its shocking success and the Wall Street bailout produced an angry and shockingly successful populist protest movement in the Tea Party, which has far outlasted its expected shelf life. In 2009, after the regime in Tehran denied the antiregime election results, millions of Iranians, especially young ones, protested for weeks. The Web and social media were key tactical tools in all three instances. But they seemed at the time to be one-offs, not prefaces to an epochal turn of history's wheel.

The Iranian regime's suppression of the Green Revolution must have reassured the dictators and monarchs in the Arab Middle East and North Africa and, you'd think, dispirited would-be democratic freedom fighters in those countries. The global spread of liberty hit a plateau a dozen years earlier, according to the international monitoring organization Freedom House. And the Middle East and North Africa remained the world's tyranny belt: at the end of 2010, Freedom House declared three-fourths of the Arab countries "not free" — including Tunisia and Egypt. In Arab countries, the prosperity of the past decade — Egypt's economy grew by 5% and more, even during the recession — was not widely shared; rising expectations that go unfulfilled are sociology's classic explanation for protest. For a critical mass of people from Cairo to Madrid to Oakland, prospects for personal success — for the good life at the End of History that they'd been promised — suddenly looked very grim. They were fed up, and the frustration and anger exploded after the regimes overreached.

In short, 2011 was unlike any year since 1989 — but more extraordinary, more global, more democratic, since in '89 the regime disintegrations were all the result of a single disintegration at headquarters, one big switch pulled in Moscow that cut off the power throughout the system. So 2011 was unlike any year since 1968 — but more consequential because more protesters have more skin in the game. Their protests weren't part of a countercultural pageant, as in '68, and rapidly morphed into full-fledged rebellions, bringing down regimes and immediately changing the course of history. It was, in other words, unlike anything in any of our lifetimes, probably unlike any year since 1848, when one street protest in Paris blossomed into a three-day revolution that turned a monarchy into a republican democracy and then — within weeks, thanks in part to new technologies (telegraphy, railroads, rotary printing presses) — inspired an unstoppable cascade of protest and insurrection in Munich, Berlin, Vienna, Milan, Venice and dozens of other places across Europe, as well as a huge peaceful demonstration of democratic solidarity in New York that marched down Broadway and occupied a public park a few blocks north of Wall Street. How perfect that the German word Zeitgeist was transplanted into English in that unprecedented, uncanny year of insurrection.

During the battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954, just as the French colonialists were about to lose to the communist revolutionaries and leave Indochina, President Dwight Eisenhower held a news conference. "You have a row of dominoes set up," he said, positing Vietnam as the domino between fallen China and North Korea and the rest of Asia. "You knock over the first one, and what will happen to the last one is the certainty that it will go over very quickly." But in 1975, after the communists won in Vietnam and Cambodia, no other countries followed, and the domino theory of contagious national-liberation movements was discredited forever.

Forever, until now. This is how the dominoes fell in 2011 — and these are some of the people who pushed them.