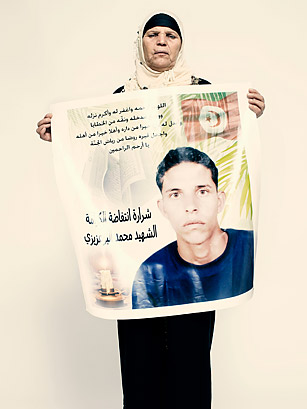

"Mohamed suffered a lot. He worked hard. But when he set fire to himself, it wasn't about his scales being confiscated. It was about his dignity."

—Mannoubia Bouazizi, Tunisia

(7 of 8)

In both Egypt and Tunisia, the freely elected new parliaments will be dominated by Islamists — sweet-talking moderates who secularists worry won't stay that way. But as Tantawy of the Muslim Brotherhood told me, "It's not just liberals vs. the Brotherhood now. The Islamists disagree among themselves." To me, the mainstream Islamist parties in Egypt and Tunisia don't appear much more fanatically religious than, say, Pat Robertson–esque Evangelicals in the U.S., and unlike the Republican hard-liners, they sound committed to a national consensus that includes secular liberals. "Democracy is a new culture, and we have to get used to it," says Abdelhamid Jlassi, a Tunisian Islamist leader who spent 17 years as a political prisoner. "Now we have to get used to being hit by eggs."

And the secular revolutionaries remain hopeful that they will not turn out to have been useful idiots to new oppressors. Shadi Taha is a U.S.-educated civil engineer and major liberal Egyptian party official who's running for parliament on a coalition slate with Muslim Brothers. "I don't agree with some of their things," he told me, "but in the 1980s, before they got into politics, they were as crazy as the Salafis" — the fundamentalists who are winning a quarter of the current parliamentary vote. He thinks democratic politics has an inherently moderating effect. Even Tunis University professor Dalenda Largueche, a feminist who could barely contain her horror at ascendant Islamism when we spoke, can eke out some hope. "They want to change Tunisia according to their vision," she says, "but Tunisia will change them." The secularists have a founding-fathers-and-mothers faith in freedom and democracy that is stirring: there's no going back to tyranny, they're sure. "In the end," Wael Nawara says, "things will turn out all right, because the relationship between people and authority in Egypt has changed forever. People discovered that they can change and stop authority from going too far. That self-discovery changes everything. They learned they can replace a ruler. That's the revolution."

Yet there is, for now, a self-sabotaging catch-22 operating among protesters all over the world. All the protests have been against systemic status quos. That has been their great strength. "If it was politicians who had led the movement," Jlassi says of the Tunisian revolution, "it wouldn't have succeeded, whereas the youths, who were unaffiliated, could appeal to everyone." But because even free politics can be inherently unclean, the youth and other liberals don't yet have the stomach for democratic hardball. Will the moral high ground keep working for them? It would be pretty to think so. U.S. Occupiers lack faith in the occupant of the Oval Office and aren't entirely thrilled with their labor-union allies, and the indie generations' need for absolute consensus can devolve into a feckless Bartlebyism — passive resistance, preferring not to.

Ditto in Europe and the Arab countries. In Tunisia, says Lina Ben Mhenni, "we didn't complete the revolution. We got rid of the dictator. Maybe the mistake that we made was that most of us rejected the idea of entering political life." Absent dictatorships to overthrow, idealistic purity can carry a high political price, and if you leave the dull but essential business of governing to the squares and grownups, you lose.

On the other hand, one of the unequivocal generational virtues of these movements has been their use of the Internet and social media. Two years ago, scholars Nicholas Christakis (Harvard) and James Fowler (University of California, San Diego) published Connected, a groundbreaking study of social networks, which they summarize as "how your friends' friends' friends affect everything you feel, think and do." The protests of the past 12 months look like a spectacular worldwide confirmation of those findings.

Calling the Arab uprisings Facebook and YouTube and Twitter revolutions is not, it turns out, just glib, wishful American overstatement. In the Middle East and North Africa, in Spain and Greece and New York, social media and smart phones did not replace face-to-face social bonds and confrontation but helped enable and turbocharge them, allowing protesters to mobilize more nimbly and communicate with one another and the wider world more effectively than ever before. And in police states with high Internet penetration — Ben Ali's Tunisia, Mubarak's Egypt, Bashar Assad's Syria — a critical mass of cell-phone video recorders plus YouTube plus Facebook plus Twitter really did become an indigenous free press. Throughout the Middle East and North Africa, new media and blogger are now quasi synonyms for protest and protester.

And then there was the Arab Spring's other essential, not-quite-as-new media form — independent 24-hour TV news. When I asked the Islamist Jlassi why the revolution had not happened a decade earlier in Tunisia, he instantly answered, "Al-Jazeera and the Internet were the differences, especially al-Jazeera — everybody watches TV."