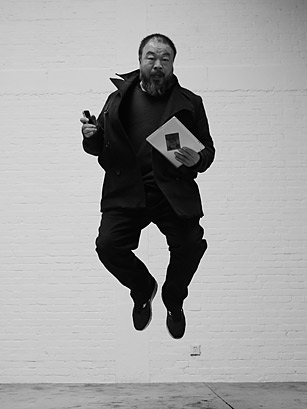

For 81 days last spring and summer, Ai Weiwei was China's most famous missing person. Detained in Beijing while attempting to catch a flight to Hong Kong on April 3, Ai, an artistic consultant for the iconic Bird's Nest stadium, was held almost entirely incommunicado and interrogated some 50 times while friends and supporters around the world petitioned for his release. On Nov. 1, Ai, who says the case against him is politically motivated, was hit with a $2.4 million bill for back taxes and penalties. Two weeks later, he paid a $1.3 million bond with loans from Chinese supporters who contributed online and in person and even tossed cash over the walls of his studio in northeast Beijing.

The son of a revolutionary poet, Ai, 54, has grown more outspoken in recent years, expressing his anger at abuses of power and organizing online campaigns, including a volunteer investigation into the deaths of children in schools that collapsed during the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. His detention came amid a broad crackdown on activists by the Chinese government meant to stamp out a call for Arab Spring–inspired pro-democracy protests as well as continuing unrest in the Tibetan regions, where 12 people have set themselves on fire since March to protest Chinese policies.

Ai, who speaks excellent if not quite flawless English, sat down on Dec. 12 with TIME's Hannah Beech and Austin Ramzy — and a calico cat, one of nearly two dozen cats and dogs at his studio — to discuss his detention, the poetry of Twitter and whether China is immune to the global forces of protest and revolution.

In 1981 you left China with no plans to return, but you came back. Why?

Before, I had seen my father and other people criticized or struggled against, but I was not directly involved. Then you see your generation being crushed. You see that this power has no intention of telling the truth. On the one hand it is ruthless, but on the other hand it is so weak.

When you are 20-something years old, you realize the only way to protect your dignity is to leave rather than to be damaged by this big machine. You see in your generation people who are destroyed. So I decided I had to leave.

After 12 years in New York, I was 36. I heard a lot about how China was different. My father was ill. I wanted to go back to China and pay my last respects.

You returned in 1993. How is today's China different from the one you left?

I think two things have changed China. To survive, China had to open up to the West. It could not survive otherwise. This was after many millions have died of hunger in a country that was like North Korea is today. Once we became part of global competition, we had to agree to some rules. It's painful, but we had to. Otherwise there was no way to survive. But domestically it's still the same machine. There's no judicial process or transparency.

The other is the Internet. They realized that it was also important to surviving. It's also related to survival. But to use it, they had to open up. They could not completely censor the information and the knowledge available there. These two things completely changed the character of this nation.

In recent years, you have merged the Internet with political activism. How did that happen?

I got involved with architecture. To work in architecture you are so much involved with society, with politics, with bureaucrats. It's a very complicated process to do large projects. You start to see the society, how it functions, how it works. Then you have a lot of criticism about how it works.

Because of my work in architecture, Sina [a Chinese Internet company] asked me to blog. I told them I don't have a computer. I don't know how to type. They said, "Don't worry, it's easy. We can help you set it up." At the beginning, I started to post my early artworks. I only wrote a few articles. Even though writing is the most admirable skill, I had no chance to become a writer because of my educational background. I hadn't really studied it except for Chairman Mao's sentences. So I just started to type. My first blog post was one sentence, something like "To express yourself needs a reason, but expressing yourself is the reason."

Later I became very involved in writing. I really enjoyed that moment of writing. People would pass around my sentences. That was a feeling I never had before. It was like a bullet out of the gun.

Your work online became more political, particularly after you launched your investigation into the shoddily constructed schools that collapsed in the Sichuan earthquake.

They shut off my blog because every day we were posting investigations. I said it was O.K. if the government didn't want to tell the truth, but citizens should bear the responsibility to act. That is very powerful. We showed the people how we got those [student] names, what were the difficulties [the volunteers] encountered, how many times we had been arrested, how we searched — all the details.

I was very sad the moment they shut it off, because there was nothing we could do. And then some guy said, "I opened a miniblog for you." It was just one sentence — 140 characters. Twitter was like a poem. It was rich, real and spontaneous. It really fit my style. In a year and a half, I tweeted 60,000 tweets, over 100,000 words. I spent a minimum eight hours a day on it, sometimes 24 hours.

Your detention forced you into silence. What was it like?

First they make sure you know that nothing can protect you, no law can protect you. They gave me the example of Liu Shaoqi [the Chinese head of state who was persecuted during the Cultural Revolution and died in prison in 1969]. The constitution could not protect him, and today not much has changed. Then they said, "We want to dirty your name. We want to smash your popularity. We want to tell people you're a liar and dishonest."