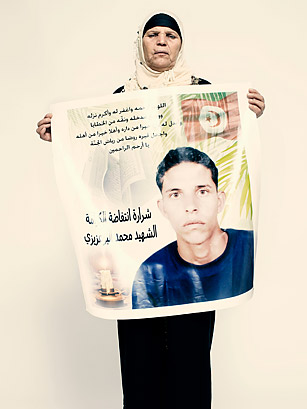

"Mohamed suffered a lot. He worked hard. But when he set fire to himself, it wasn't about his scales being confiscated. It was about his dignity."

—Mannoubia Bouazizi, Tunisia

(4 of 8)

The regime's violent response surprised no one. As in Tunisia, when the crackdown escalated — from tear gas to rubber bullets to real bullets, to Ghonim's detention for the duration, to a nationwide shutdown of Internet connections, to armed camel riders rampaging through Tahrir — so did the number of protesters in Cairo and all over the country. At least 4.5 million Egyptians protested during those three weeks — in other words, 8% of the population over 14.

Hisham Kassem, a prominent 52-year-old independent journalist and publisher, had never been part of a street protest before. He is bracingly clear-eyed, a stiff-necked curmudgeon. On Jan. 28 he was teargassed and, he told me, still sounding amazed 10 months later, threw rocks at police. "I saw people shot next to me." When he returned on "the day of the camel attack, it was war — I almost got mauled to death by the thugs." And another day when he arrived at Tahrir, "This kid asked for my ID: 'Whose side are you on?' I said, 'What the hell do you mean?' " But then and there on the edge of Liberation Square, he had an epiphany: he may have been a longtime pro-democracy VIP, but this was now democracy. "I felt a strange acceptance," he says. "I didn't begrudge them."

By then the army had announced, "Your armed forces, who are aware of the legitimacy of your demands ... will not resort to use of force." President Hosni Mubarak was finished — "Please go," a Tahrir protest sign urged, "because I want to take a shower" — but it took 11 more days for Mubarak to pass through denial, anger, bargaining and presumably depression to arrive at the acceptance stage. "The day Mubarak stepped down," says Abdo Kassem, 25, an unemployed Cairene who'd never been politically active until he followed the Facebook protest instructions last January, "I was crying. For me, that was like bringing down a fake god."

Millions protest. Armies stand down. Dictators leave. Impossible fantasies two months earlier — now they were coming true. The "days of rage" meme and democratic dream had achieved breathtaking momentum, spreading not just to the softer monarchical dictatorships — Jordan, Bahrain, Morocco — but also to Yemen, Algeria and the hardcore police states Syria and Libya.

In the spring, they spread to Europe. On May 15, tens of thousands marched to Madrid's Puerta del Sol plaza, along with tens of thousands more in dozens of other cities, united by slogans like "We are not goods in the hands of politicians and bankers." They were frustrated by unemployment, a lack of opportunity and politics headed nowhere. They called themselves Los Indignados, the Outraged.

Spain's one-day march turned into a months-long self-governing encampment — one of the new defining characteristics of 2011's brand of communal resistance. Throughout the country, about 6 million out of a population of 46 million participated in Indignados protests. Among those in Madrid was Olmo Gálvez, 31, an Internet entrepreneur just back from three years working in China and new to politics. He'd helped set up social-media networks for the protest. "It was marvelous to see people become the actors in their own lives," he says. "You could watch them breaking out of their passivity."

Ten days after the Madrid protests began, the contagion spread to Greece. George Anastasopoulos, 36, has a Ph.D. in sociology but earns his living as a DJ. "That first Sunday when we saw 100,000 people show up, we were overwhelmed," he says of the Athenians' camp in Syntagma Square, in sight of Parliament. "And then the second Sunday, 500,000 people showed up. That enthused us so much, and we started dreaming really big."

"Our protests," says Christina Lardikou, a 31-year-old Athenian who works in fashion, "all started from the Indignados." But they drew from other inspirations too. Among the chants in the birthplace of democracy last spring were "Yes we can!" And Anastasopoulos has kept a banner reading "Let freedom ring" — that is, a quote from Martin Luther King Jr. quoting "My Country 'Tis of Thee."

The Greek protests continued for more than a month, until just about the time 150 young Israeli protesters started pitching tents in the median of Rothschild Boulevard in Tel Aviv. The grievance package was familiar: good jobs too scarce, cost of living too high, politicians corrupt, only the well-connected rich getting richer. Soon there were 100 such encampments all over Israel, in working-class towns as well as yuppievilles. For a finale in early September, an estimated 400,000 of the country's 7.7 million citizens marched, chanting, "The people demand social justice!" When the Egyptian revolutionary leader el-Ghazali Harb told me how pleased he was that Tahrir Square had inspired copycat protests all over the world, I asked if his pride extended to Israel. He laughed and said, "I will say we were happy about that as well."