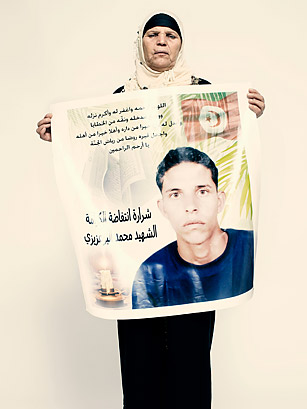

"Mohamed suffered a lot. He worked hard. But when he set fire to himself, it wasn't about his scales being confiscated. It was about his dignity."

—Mannoubia Bouazizi, Tunisia

(3 of 8)

The Year of Protests

The fire didn't kill Mohamed Bouazizi right away. Passersby doused the flames and took him to the hospital. He was still alive, barely.

That afternoon, other produce sellers and townspeople joined the Bouazizis in protest outside the governorate. A cousin posted a video of the demonstration. Word spread thanks to al-Jazeera and the Internet — a third of all Tunisians use the Internet, and three-quarters of those have Facebook accounts — inspiring protests in other towns and cities. After Bouazizi died on Jan. 4, the protests reached a critical mass, and more than a dozen protesters around the country were killed by police. "I'd watch TV," Basma Bouazizi told me, "and say, 'God, the Tunisian people have woken up!' "

Spontaneous protests? In 2011? In an Arab police state? Heroic, hopeless, doomed. Three weeks in, the nearly universal presumption about the protests' implications was summed up in the Economist's first report: "Tunisia's troubles are unlikely to unseat the 74-year-old president or even to jolt his model of autocracy."

Lina Ben Mhenni, 28, a linguistics teacher at Tunis University, had been blogging for a few years about Tunisian censorship and election rigging under the name "A Tunisian Girl." She went to the town of Regueb, 25 miles from Sidi Bouzid, to photograph a young protester who had been shot dead and uploaded the image. "On that day I lost my fear completely," she says. "I was ready for anything, even death." By the end of the week, she was back in Tunis, protesting outside the old white stucco casbah that served as the seat of government. So was Hilme al-Manahe, 23, an unemployed baker. His mother, Sayda al-Manahe, says Bouazizi's self-immolation had galvanized Hilme. "He used to say, 'This poor man — I can understand why he did that. He just wanted to earn a living. His story is like my story, which is like my friend's story.'"

"I would tell him," Sayda says, "Be quiet, sit down, and don't even think about getting involved in this." But on Jan. 13 he went to the demonstration in Tunis. He had just recorded a friend with his cell phone when a bullet, presumably fired by a police sniper, pierced his heart.

The next morning, Majdi Calboussi, a middle-class 29-year-old software developer and antiregime blogger, was there recording the protests and the police with his BlackBerry. "People started to say, 'Ben Ali, dégage' " ("Get out, Ben Ali"). He uploaded his video to Twitter, and it got half a million views in a day. Hours later, President Zine el Abidine Ben Ali flew to exile in Saudi Arabia. After just four weeks, the protesters had won. And the next domino was struck.

Among all the Egyptians I met, there is absolute agreement about one thing: Tunisia was the spark of their revolution. "It wouldn't have happened without them," says Shady el-Ghazali Harb, a 32-year-old surgeon who was one of 13 main leaders in Tahrir Square. The lessons of Tunisia weren't just inspirational; they were practical. "This was like a user's manual in how to topple a regime peacefully," says Wael Nawara, 50, a Web entrepreneur and longtime opposition political activist. In January, Tunisians "sent us a lot of information," says Ahmed Maher, a Cairo civil engineer and one of Egypt's most prominent activists, "like use vinegar and onion" — near one's face, for the tear gas — "and how to stop a tank. They sent us this advice, and we used it."

The Egyptians had their own Mohamed Bouazizi: an underemployed middle-class 28-year-old named Khaled Said. One day last year, after apparently hacking a police officer's cell phone and lifting a video of officers displaying drugs and stacks of cash, he was arrested and beaten to death. Wael Ghonim, then a 29-year-old Google executive, created a Facebook page called We Are All Khaled Said to memorialize him. It went viral, and in January, Ghonim returned from Dubai to Egypt to help plan a protest set for Jan. 25: a "day of rage" in Tahrir Square. Maher and other activists were invited to collaborate. They met online and face to face to work out the details. Brinjy told me she "was terrified. I thought we'd try but run away if necessary. Then we ran into huge crowds heading to Tahrir, and I knew it was going to be big."

"From the start I thought it would succeed," 29-year-old filmmaker Mohammed Ramadan says. "In my whole life I'd never seen protests like that. Girls! Some wore hijabs, some didn't, Christians, Muslims — I'd never seen that." The Muslim Brotherhood hadn't endorsed the protest, but Khaled Tantawy, a 34-year-old Brotherhood apparatchik, came anyway. He also was struck by the diversity. "I saw all these different and surprising kinds of people protesting and thought, Wow, this can happen."

That night it happened. "The surprise," according to Mohamed el-Beltagy, a member of the Brotherhood who went to Tahrir unofficially, "was that there was a new generation who could break the fear barrier. At midnight, when the [police's] violent clearing of the square happened and the protesters didn't run away and go home, I knew it was a revolution."