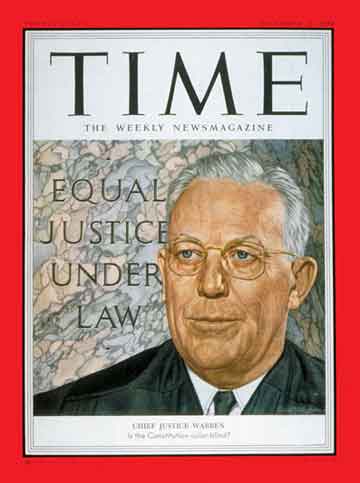

Chief Justice Earl Warren

(7 of 8)

It is much too early for anyone to tell what kind of Chief Justice Earl Warren will be. Only time will reveal that. He is neither a philosopher like Oliver Wendell Holmes nor a master of his fellow men equal to Charles Evans Hughes. But he has a good mind, a wealth of practical experience and success in administering the law, a feeling for the human side of a case and boundless energy.

No doubt one of the first major entries that will be written on Chief Justice Warren's record is the court's action in the school segregation case. The decisions will directly affect some 12 million schoolchildren in at least 17 states* and the District of Columbia. The decisions may change the whole pattern of life in the South. In many nations where U.S. prestige and leadership is damaged by the fact of U.S. segregation, the court's action is awaited with intense interest.

In the South, some states have threatened to take drastic steps if the court bans segregation. South Carolina's Governor James Byrnes and his legislature already have on the books a "preparedness law" ready to abolish the public-school system. In Georgia, Governor Herman Talmadge and his legislature are also ready to turn the schools over to private organizations.

Many Southern states have been rushing to meet the separate-but-equal standard (South Carolina has allocated $84.3 million for new schools since April 1951, 68% of it for Negro schools), and in some districts Negroes now have the best schools. But most white leaders in the South are not ready to take the next step: desegregation.

No longer do the Southern defenders of segregation take their stand with Ben Tillman on the flat assertion of racial superiority. Nowadays they stress the "practical" consequences of mixed schools. Last week John W. Davis told the court that Clarendon School District No. 1 in South Carolina has 2,799 Negro and 295 white Children of school age. If these children are mixed, the schoolrooms will contain nine Negro children to each white child. Asked John Davis: "Would that make the children any happier? Would they learn any more quickly? Would their lives be more serene?"

One point that was obviously worrying the Supreme Court was the question of timing. If the court bans segregation, should the new principle apply immediately? Or should there be a transition period? Should the Supreme Court lay down specific time limits and rules? Or should it leave details to the lower courts? Both Justices Robert Jackson and Frankfurter mused on these points as the attorneys argued last week.

Jackson: I foresee a generation of litigation if we send it back with no standards . . .

Frankfurter (later) : I do not see how you can escape some of the things which worry my brother Jackson . . .

Jackson: They do not worry me; they will be worrying our children.

The Great Success Story. No matter which way Chief Justice Earl Warren and the eight Associate Justices decide these cases, the race problem will be there in some form to worry future generations of Americans.