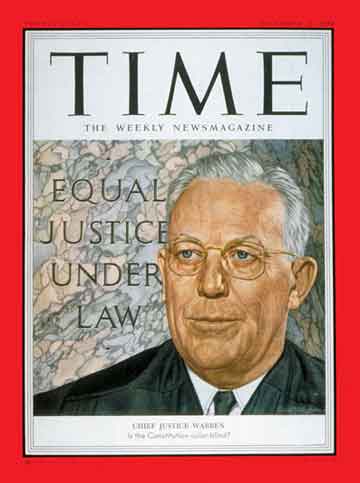

Chief Justice Earl Warren

"If one race be inferior to the other socially, the Constitution of the United States cannot put them on the same plane"

—From the majority opinion of the U.S. Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson, 1896.

"But in the view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste system here. Our Constitution is color-blind."

—Associate Justice John Marshall Harlan, dissenting in the same case.

At the stroke of noon, one day last week, Chief Justice Earl Warren strode through the red velour draperies that hang behind the long mahogany bench of the U.S. Supreme Court. As the Chief Justice and his eight associates took their places, Earl Warren's broad, friendly face broke into a quick smile. He beamed at Mrs. Warren, who had arrived from California the night before and was sitting among the spectators nearest the bench. For 65 minutes the court went through routine business. But in spite of the Chief's pleasant demeanor, there was an air of tension in the marble-columned courtroom.

The Supreme Court was about to hear final, oral arguments on one of the most momentous issues to come before the court in its 164-year history, perhaps the most important question that ever came before a Chief Justice so early in his tenure. The crucial question: Should segregation in the public schools be abolished?

"The Key of History." As the arguments began, every seat (300) in the world's most important courtroom was occupied. Negro lawyers sat next to white lawyers. Negro reporters sat next to white reporters. Negro spectators sat next to white spectators. But the fact that the color line has not been erased in the U.S. was soon apparent.

Speaking for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Thurgood Marshall, eminent Negro constitutional lawyer, told the court that the defenders of school segregation were asking for "an inherent determination that the people who were formerly in slavery . . . shall be kept as near that stage as possible." Said the big, deep-voiced Thurgood Marshall: "Now is the time . . . that this court should make it clear that that is not what our Constitution stands for."

On the other hand, John W. Davis, dean (80) of the nation's constitutional lawyers, arguing for segregation, maintained that separate schools are not only constitutional but often better for the Negroes. Representing the state of South Carolina, the white-haired Davis told the court: "Recognize that for 60 centuries and more, humanity has been discussing questions of race and race tension . . . Disraeli said, 'No man will treat with in difference the principle of race. It is the key of history.' "