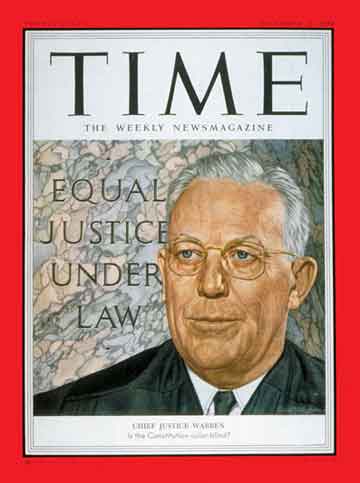

Chief Justice Earl Warren

(5 of 8)

"One Law for All." To this first historic case of his tenure, the new Chief Justice of the U.S. brought a well-illustrated attitude of racial tolerance. Earl Warren grew up in Bakersfield, in California's San Joaquin Valley, where segregation was unknown. At the University of California, one of Warren's good friends was a Negro named Walter Gordon ("We used to box a bit together," Gordon recalls). A boxing, wrestling and football star (All-America, 1918), Gordon later coached Warren's son James at the university. In 1944 Warren appointed Gordon a member of the State Adult Authority, which sets all prison terms and grants all paroles.

Not long after he became governor of California in 1943, Warren laid down a rule: "I don't want to hear of any of my department heads refusing to hire anyone for reasons of race, color or creed." Among Warren's own appointments was Edwin L. Jefferson, the first Negro ever named to California's Superior Court. To each of the California legislative sessions, from 1945 through 1953, Warren proposed, in one form or another, a state agency to assure fair treatment of all races. The proposal was rejected each time, but Warren personally stuck to the stand he had taken as a candidate for Vice President in 1948: "We must insist upon one law for all men . . . Anything that divides us or limits the opportunities for full American citizenship is injurious to the welfare of all."

Last year Warren volunteered a view on a race problem when residents of an all-white neighborhood of South San Francisco forced a Chinese family to move out (TIME, Feb. 25, 1952). Warren wrote the family: "I am not at all proud of the action of the people in the neighborhood of your new home . . . I agree with you it is just such things that the Communists make much of in their effort to discredit our system."

A Sick Feeling. Earl Warren's own views on the race question do not necessarily indicate that he will vote to ban segregation in the schools. Some lawyers who are against segregation nevertheless maintain that each state should have the right to fix its own educational policies. In weighing such questions of law, Warren can call on wide experience as a prosecutor and administrator, but little background in private law practice, and no previous service on the bench. He was in private practice for just three years after he graduated from law school, and once admitted that court appearances terrified him. Said he: "I'd get on a streetcar, and I'd be so tense I would hope the car would be wrecked on the way to the courthouse."

Later, as a deputy city attorney for Oakland, deputy and district attorney for Alameda County (Oakland, Berkeley, Alameda) and attorney general of California, he showed no signs of terror in or out of court. He was a relentless prosecutor, convicted an average of 15 murderers a year, chased grafters out of office and into prison. But he drew no particular joy from his victories in criminal cases. Said he: "I never heard a jury bring in a verdict of guilty but that I felt sick at the pit of my stomach."