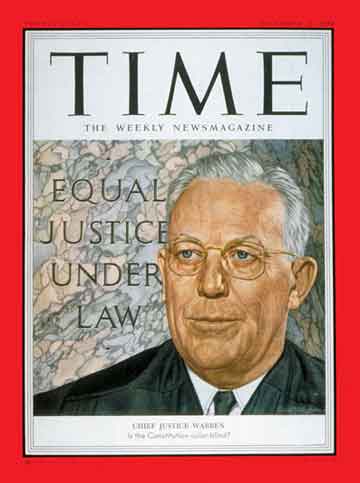

Chief Justice Earl Warren

(6 of 8)

As governor, Warren greatly improved the caliber of the California bench by appointing well-qualified judges. Always a practical man rather than a philosopher, always busy as an administrator, Warren never expounded a full-bodied philosophy of law. Los Angeles Attorney Robert Kenny, opposing Warren for the governorship in 1946, charged: "He never had an abstract thought in his life."

The fact that Warren was neither a legal philosopher nor an experienced judge-did not deter Attorney General Herbert Brownell Jr. and President Eisenhower after they had finished combing the list of prospects for a successor to the late Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson last fall. They knew that Warren had been highly successful as an administrator of the second most populous and fastest-growing state, and that the court needed an administrator almost as much as it needed a strong legal philosopher.

Walks at Midnight. Sitting as Chief Justice of the U.S. is a basic change in Earl Warren's life. A hearty, friendly man who likes people, Warren used to travel up and down the State of California, meeting people, handling dozens of administrative problems through a large staff. Suddenly, he was behind a desk in an office full of law books. Warren found that he liked the new opportunity for reflection and analysis. To offset the confining nature of his work, the Chief Justice often walks for two or three miles before going to bed about midnight.

Temporarily, his family stayed behind in California. He found himself forced to eat in restaurants, which he hates to do. Said the Chief Justice: "I've never been so lonely in my life."

At the court, Warren moved in with a friendly and casual air. When he takes a breather from work at the neat desk in his oak-paneled office, he often strolls through the building greeting surprised employees with a hand outstretched and a self-introduction: "I'm Earl Warren." Said one guard: "He shakes more hands in one day than many other Justices do in five years."

When he wants to discuss a point with another Justice, he doesn't call the Associate in. He telephones and asks: "I've got a point to check with you. May I come over?"

One Hand Tied. Warren writes most of his own notes and memorandums (and the one opinion he has written so far) with a yellow lead pencil on standard, yellow, lined legal pads. He writes with his right hand, although he is naturally a left-hander (he was once a southpaw outfielder on a sandlot baseball team). When he was a schoolboy, a teacher tied his left hand behind him and forced him to write with his right. This practice, long condemned as psychologically disturbing, has left no noticeable scars on the Chief Justice of the U.S.

The other Justices have considered their new chief and have reached a favorable opinion. It might be summed up: he has made a good start. Perhaps the best illustration of this came the day that Warren dared to rephrase a question asked in open court by Justice Frankfurter. Old hands around the court tensed; one does not say "in other words" to peppery Felix Frankfurter. But Justice Frankfurter, accepting Warren's paraphrasing, said: "Precisely, yes, yes . . ."