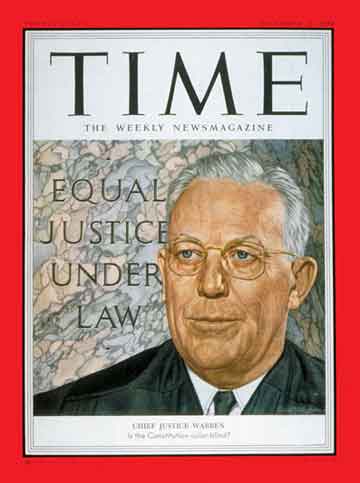

Chief Justice Earl Warren

(2 of 8)

Through eleven hours of argument, the nine Justices were studies in intense interest. Earl Warren, his bulk (6 ft. 1 in., 215 Ibs.) dominating the bench, sat erect in the high-back chair that had been used by the late Chief Justice Vinson (Said Warren to a court official who asked him if he wanted his own specially built chair: "Pshaw, that one's plenty good enough for me!"). Occasionally he asked a quiet question to clarify a point. Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter, as if playing pizzicato violin to Warren's cello, turned and twisted in his specially built chair, fired quick, needling questions at the attorneys, sent messengers scurrying for law books. All of the nine men behind the long bench, unlikely to agree, knew that they faced a decision that could well be a landmark in the history of race relations.

Opposite the Pawn Shop. While eminent legal minds considered the great issue, Spottswood Thomas Boiling Jr., 14, sat with the all-Negro sophomore class in Washington's new Spingarn High School, quietly tending to his studies. Spottswood Boiling's name will go down in history with the segregation cases, for he is one of the plaintiffs. His case is a resume of the issues involved.

Its history began one day in 1950, when Spottswood and eleven other Negro children, with a police escort and a battery of lawyers, went to Washington's shining new John Philip Sousa Junior High School. The spacious brick-and-glass school, facing a carefully groomed golf course in southeast Washington, is in a solid residential district. It has 42 bright classrooms, a fine 600-seat auditorium, a completely equipped double gymnasium, a playground with room enough for seven basketball courts and a softball diamond.

Some of the classrooms were empty, but the principal, Miss Eleanor P. McAuliffe,* refused to admit the Negro children. She had to refuse. District of Columbia officials interpret a law, passed by Congress in 1862, as requiring segregated public schools.

Spottswood Boiling went, instead, to Shaw Junior High School for Negroes. It is an old, dingy, unsanitary, ill-equipped building across the street from The Lucky Pawnbroker's Exchange. Built in 1902, and used as a white school until 1928, Shaw has an L-shaped playground too small for a ball diamond, a welding shop turned into a makeshift gymnasium, a science laboratory fitted out with a Bunsen burner and a bowl of goldfish.

The contrast between the two schools was clear, but even if Shaw had been just as good a school as Sousa, the parents of Spottswood Boiling and his friends would not have been satisfied. They were attacking something deeper than disparity of facilities. Their target was the principle of segregation. Said Spottswood's widowed mother, Mrs. Sarah Boiling, a $57.60-3-week bookbinder for the Federal Government's General Services Administration: "I think that to know how to deal with all people you've got to start as a child in school. In school you learn to get along . . . Colored people learn to get along with white people, white people get to understand colored people, or they would if they went to school together as children."