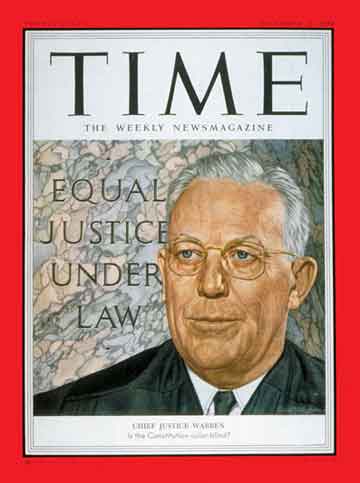

Chief Justice Earl Warren

(4 of 8)

Southern states immediately began returning to the "Black Codes," pre-14th turning to the "Black Codes" Amendment laws designed to keep the Negro in a status not far removed from slavery. There came to power in the South politicians such as "Pitchfork Ben" Tillman, governor and later Senator from South Carolina, who publicly proclaimed that the Negro was biologically inferior to the white man. When "inoculated with the virus of equality," said Tillman, the Negro became "a fiend, a wild beast, seeking whom he may devour."

Along the rutted road back from Pitchfork Ben's heyday, a great argument has developed about just what kind of equality Congress and the state legislatures meant to give the Negro through the 14th Amendment. Its language seems sweeping enough, but many lawyers are impressed by the fact that it contains no specific declaration on segregation. That point has become important in the cases now before the Supreme Court.

Last spring, after reading the briefs, the high court asked the attorneys to study and discuss whether the framers and ratifiesr of the 14th Amendment meant to abolish segregation in the schools. The court got three answers. Thurgood Marshall, for the N.A.A.C.P., said that was clearly the intention. John W. Davis, for South Carolina, said that was clearly not the intention. Assistant U.S. Attorney General J. Lee Rankin said that the evidence was inconclusive, but that on other grounds, the U.S. Government favored an end of segregation.

Can Separate Be Equal? The U.S. Supreme Court has never spoken directly on the subject of segregation in the public pre-college schools. The decision that has long been used by Southern states as the guide on segregation is Plessy v. Ferguson, a transportation case. It arose on June 7, 1892, when Homer Adolph Plessy bought a ticket on the East Louisiana Railroad, from New Orleans to Covington, La. Plessy, seven-eighths white and one-eighth Negro, took a seat in the white coach on the segregated train. When he refused to move, he was taken off and jailed. The case reached the Supreme Court in 1896, and the court ruled that Louisiana's law, calling for "equal but separate" facilities on trains, was constitutional. The majority opinion held that Negroes were equal to whites "civilly and politically," but not "socially."

At higher educational levels, the separate but equal doctrine has been considered by the Supreme Court. The first major case came in 1938, when the Supreme Court ruled that Negro Lloyd Gaines should be admitted to the University of Missouri Law School because he could not find equal facilities anywhere else in .his state. This and other similar cases that followed opened the doors of many graduate and professional schools to Negroes.* But none of the cases reached the level or the principle involved in the present cases. The Negro spokesmen maintain that even if physical facilities are the same, social and psychological factors make a basic difference. Their contention: "separate" can never be "equal."