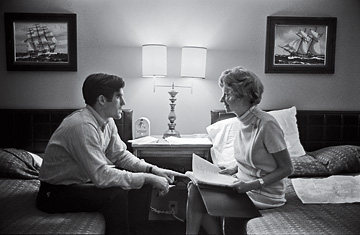

On the campaign trail during his mother's Senate bid, Mitt and Lenore strategize in a hotel room

Square jaw set, white mane swept back, George Romney stormed into the Lansing Civic Center one day in November 1970, spoiling for a fight. His wife Lenore had just lost an ill-advised campaign for the U.S. Senate. Her husband blamed disloyal Republicans--Michigan Governor William Milliken most of all. George said privately that Milliken had "weaseled and, frankly, destroyed my wife as a candidate." Now he grabbed a microphone and denounced the room at large, where GOP leaders had gathered in Milliken's honor.

Silence fell. George set his eyes on Joyce Braithwaite, a 30-something party activist and an intimate of Lenore's. He leaned in, pushed a thick forefinger toward her and demanded that she admit he was right. Braithwaite demurred. George raised his voice and insisted.

Lenore, standing alongside him, burst into tears. The campaign had drained her, body and spirit, and "she was horrified that George was behaving that way in public," a witness recalls. About the same time, she sent a letter to her friend Elly Peterson. "'Total Forget' is the only prescription to keep from total dissolvement," Lenore wrote of her campaign travails. "But my subconsciousness isn't obedient. I still waken after a nightmare of seeing myself in print as distorted by our 'friends.'"

Thus fell the Romneys from political grace. One, charismatic and headstrong, was a powerful three-term governor who self-destructed in the 1968 presidential campaign. The other, a widely admired state first lady, began her Senate race two years later as a "love affair between me and the people of Michigan" and ended it with the lament that "it's the most humiliating thing I know of to run for office."

Mitt Romney, the youngest of four children, was deeply engaged in his mother's campaign, far more than the ones his father ran when Mitt was young. He accompanied her on hundreds of campaign stops, driving together across all 83 Michigan counties in a blue truck festooned with lenore signs. When reporters asked about his future, Mitt mapped it precisely. First he would seek his fortune, then "I might consider politics," he told the Saginaw News that summer, his standard reply. "I just wouldn't want to have to feed my family from money made as a politician."

No presidential nominee until now has grown up with two parents who ran for high office or so much early exposure to the craft. Their public ruin seared him and schooled him. The lessons he drew have shaped his ambitions, his calculations of risk and his strategy for achieving what his mother and father could not. Bluntly put, Mitt learned from each of his parents how to lose an election. He found much to emulate as well, but longtime associates and family members say it became his prime concern to avoid their mistakes. As he constructed a political persona, they say, his father's career loomed large--but his choices owed more to Lenore than to George.

Outwardly, Mitt followed his father's arc from business to politics. George bequeathed him ambition and stamina, and Mitt knew what kind of punishment to expect. "I don't look forward to a political career, because it's a shame the way the people slander someone who has chosen to enter public life," young Mitt told reporters on a 1970 campaign stop in Saginaw. He had little of George's appetite for war.