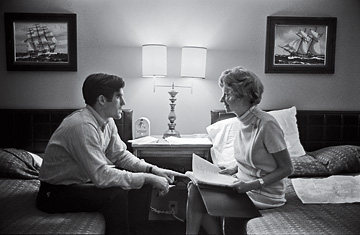

On the campaign trail during his mother's Senate bid, Mitt and Lenore strategize in a hotel room

(9 of 11)

On the stump, Lenore used the tropes of old-fashioned feminine virtue to fend off association with what one reporter said she called the "'wild' women's-lib supporters on the streets wearing no bras." In southern Monroe County, she explained her political vocation to a group of nuns by saying, "If you don't like what's being served for dinner, the only thing you can do is get in there and do the cooking yourself." She published recipes for homemade chicken salad with grapes and olives and for "baked beans Lenore" from ingredients supplied by the Michigan Bean Shippers. She explained her concern about inflation by saying, "I know what it means to the housewife."

At the same time, she challenged housewives to do more. They had "tended to be lazy intellectually," but "there just is no excuse today for women to be uneducated and uninformed," she said. Her speeches, Ballenger recalls, "were an early incarnation of feminism from the Republican side"--not Betty Friedan or Gloria Steinem but "pretty forceful in articulating the idea that women were more than just the power behind the throne."

Mitt, campaigning alongside her, reinforced the message. Posing for photographs at a tractor pull in Greenville that summer, he told a reporter, "My mother is not what you'd call a woman's liberator, but she does believe women have a contribution to make." He watched and learned as she deflected challenges with humor and nimble changes of subject or by finding something to agree with in a challenger's remarks. When men asked why she was not home with her family, she replied with lines like "Well, I've already churned the butter for today."

But Mitt also saw the damage done by verbal assaults that life had not prepared his mother for. "She was called names that somebody would have to explain to her when she got home that night," Molin says. "In factories I encountered men standing in small groups, laughing, shouting, 'Get back in the kitchen. George needs you there. What do you know about politics?'" she wrote after the election. "I tried to explain that I had always been in politics, living and working with human beings and trying to understand them."

One day in Clare, a farmer stood up and declared, "Ma'am, we don't vote for women or niggers in this county." Lenore had no answer for that. In a manuscript, she called it "the rawest example of the prejudice" she faced from the "many people--men and women--[who] openly resented the fact that a woman would even try to unseat a man." Aides and friends say the cumulative impact on Lenore was hard for Mitt to watch. On days like that, she would turn to her small entourage, one member recalls, with a lament: "Why did you put me in that situation? Couldn't you move me out of there gracefully?" Her liberal Democratic opponent, Phil Hart, who was so far ahead that he never felt the need to attack her, could be painfully condescending behind the scenes. "He would bring me a flower or a little bottle of perfume or something and say, 'I wish I could see you in a drawing room,'" Lenore told her former daughter-in-law Ronna Romney for a book on women in politics.

If she ever had a chance against the popular incumbent, Lenore was undone by her party's divisions, her growing pains as a novice candidate and the long shadow of her husband. On Election Day, Hart routed her, 67% to 33%.