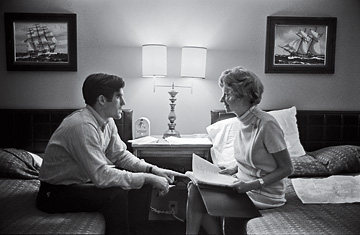

On the campaign trail during his mother's Senate bid, Mitt and Lenore strategize in a hotel room

(7 of 11)

More indignities awaited. Nixon needed a moderate in his Cabinet, and "put Romney into a meaningless department, never to be noticed again," John Ehrlichman, Nixon's counsel, wrote in his memoir. Lenore, perhaps unaware of the animus, wrote Ehrlichman to complain of "demoralizing" slights, adding that "loyalty works both ways." George served four miserable years as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, with "no effective voice" in his department, he complained to Nixon in a recorded Oval Office meeting.

An Ill-Conceived Race

No one was more surprised by her 1970 run for Senate than Lenore. For public consumption, the Romneys insisted that it was then House minority leader Gerald Ford who came up with the idea, that the Michigan GOP fell in behind her and that the family together decided to answer the call. "My husband was the last to get on the bandwagon," Lenore told Detroit magazine in April.

None of that, except possibly the nudge from Ford, was true. George was used to running things, and Nixon had him caged. From Washington, George turned his full attention back to his home state, steamrolling Lenore onto the GOP ticket. But a new guard was rising in the party, and the backlash doomed Lenore's campaign before it began. Lenore later acknowledged that her husband had ambushed her, calling the family together over Christmas 1969 without telling her why. "He said, 'What would you think if your mother decided to run for the United States Senate?' and the children all shouted, 'Go for it, Mom!' and I almost fell off my chair," she recalled. A relative tells TIME that there were always "family councils whenever there was a big decision," but George was not looking for advice. "The whole family had to stop what they were doing, pull together" for the effort.

Milliken, elevated from lieutenant governor after George's Cabinet appointment, resisted at first. He was trying to take the party reins and did not need another Romney dominating the news. Milliken maneuvered to stave off a consensus for Lenore when party leaders met on Feb. 21, 1970. Two days later, George borrowed a telephone at an Ann Arbor gas station and phoned his successor at home, threatening to denounce him at that night's Lincoln Day dinner if he failed to endorse Lenore. Milliken succumbed, but the endorsement backfired for both of them when a gas-station employee recounted the conversation to his brother, a political correspondent for the Detroit News. "Romney's reassertion of power was quick and brutal," the correspondent, Robert Pisor, wrote in a story stripped atop the next day's front page.

Lenore's chaotic launch encouraged state senator Robert Huber, a hard-right maverick from Troy, to mount a challenge for the Republican nomination. Huber criticized Lenore as a creature of bossism. He printed lurleen romney for the u.s. senate bumper stickers, alluding to a maneuver in which Alabama Governor George Wallace kept control of the state in 1966 by arranging for his wife Lurleen to succeed him. Huber slammed Lenore, too, for a secret agenda of forced integration after news accounts suggested that George Romney's HUD planned a pilot program in Warren, a blue collar Michigan suburb.