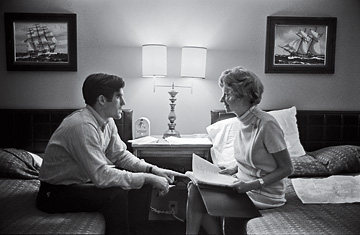

On the campaign trail during his mother's Senate bid, Mitt and Lenore strategize in a hotel room

(5 of 11)

On March 9, 1966, as the FBI's Detroit field office prepared daily surveillance reports on Martin Luther King Jr., Lenore joined him onstage before 2,000 people at Michigan State University. They chatted earnestly in view of photographers after he called for the racial integration of suburbs, which would become an explosive issue four years later in Lenore's Senate campaign.

No subject consumed her more than women's liberation, a term she disliked for its link to "burning bras and railing against male-chauvinistic pigs." She was, if not a pioneer, an early female participant in public life, but she fought looser sexual mores and glamour trends in which "sex is displayed as never before." Girls, she said, "rely too much on what I call ting-a-ling, and sure as I'm born, someone else always has more than you do ... so you're going to be done on that score." On May 3, 1968, Lenore wrote a four-page letter to Hugh Downs, the host of NBC's Today show, about the prior morning's segment on extramarital sex. "'Experts' talk about the New Morality--the morality they discuss is the barnyard morality and it is as old as the hills," she wrote.

"I know I could not have been fulfilled in my womanhood had my father said as did your guest on May 2nd that he would not hesitate to give 'the pill' to his teenage daughter," she wrote. "I cannot but weep for the child, and for others whose parents may be influenced by this 'expert' ... He forgot to tell us that sex has great emotional repercussions--that it is the most powerful and magnificent force on earth. We wouldn't permit our children to experiment with dynamite!"

Lenore struggled with her health and struggled equally to keep it out of the public eye. The details of her condition remain undisclosed even now. "She would be suddenly hospitalized," says one close relative. George "took her all over the country to major medical centers, and nobody could figure it out." Scott, then a first-year law student at Harvard, let slip to Look magazine in 1967 that his mother "has an illness few know about." At about that time, according to Fletcher, Lenore was injured outside her garage in circumstances that remain a closely guarded family secret. The following year, she fell into a bathtub and dislocated her shoulder, an injury that never fully healed. Women who read about that accident wrote to tell their own stories, and Lenore opened up to them as she seldom did to anyone. "Dear Ella," she wrote on May 9, 1968, "I am heartsick that you are in such pain. I know too well the suffering of bursitis--the months and even years that are required for the full use of the stricken arm and shoulder, and for the many hours of gripping pain all the way down to one's finger tips."

The same year, Lenore abruptly canceled her October schedule and checked in at the Jewish Hospital of St. Louis, where she saw a specialist in bone and mineral disease. "I felt fortunate to be in the intensive care unit and to be aware of all the modern equipment," she wrote afterward to her physician, Louis Avioli. "I never did get the specifics on it," says Fred Grasman, who sometimes accompanied her to political events. "She was very guarded about her health, and we were told on the campaign trail to be very solicitous if she said she needed some rest."

'A Self-Inflicted Wound'