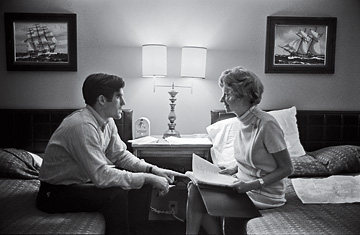

On the campaign trail during his mother's Senate bid, Mitt and Lenore strategize in a hotel room

(10 of 11)

George blamed everyone but himself, lashing out at "inaccurate press reports" that he had dragged her into the race. "The disappointing aspect of it," he said, "was to have her drafted by the party leaders and then to have the people told day after day that I had forced her on the party." Bill Goldbeck, an aide, urged him to give up the fight. "You will never convince the public that you were not the force behind Lenore's candidacy," he wrote on Feb. 2, 1971. "I did not meet or talk with a single Republican during the entire campaign who felt otherwise."

Lenore blamed no one but told one of her children, "I wish I hadn't run." To her friend Elly Peterson she wrote, "The body wounds are deep--I believe I've 'had it'--but maybe someday I'll rise again to campaign for someone I believe in ... He will have to be awfully good."

The Lessons

In the teeth of her own experience, Lenore encouraged Mitt to be that someone. Her private papers, replete with belief in a Mormon's earthly obligations, help explain why. "We as Latter-day Saint women know our vocation--know that the blessing given Abraham is ours--that our seed is indeed to be a blessing to mankind," she wrote in an unpublished manuscript in the summer of 1972. A variation on that theme made it into a speech at Mount Union College: "Each son should be able to accomplish more than his father did." George, too, touted his son as Mitt ran for the Senate in 1994, hinting at ambitions beyond. "He's better than the chip off the old block because he's had better preparation than I," he told USA Today. Neither parent lived to see Mitt win his first election as Massachusetts governor in 2002. George died at age 88 the year after Mitt lost his Senate race, and Lenore died three years after that at 89.

For Mitt, a relative says, "there was a sense of carrying the torch." With it came an understanding that he would need more strength than his mother had. "I would never run for office, that's for sure," the family member says. "It's brutal. But Mitt bounces back. He's got a resiliency that I don't have."

The purest distillate of Mitt's political education was fear of error. Mistakes invited ridicule, opened his parents to avoidable blows, fomented opposition and cost them friends. Words, a politician's most basic tools, were fraught with career-ending risk. Because Mitt in his campaigns "was the target of everybody and he couldn't blow his nose without someone taking offense, he could not make a mistake at all," says the Romney family member. "That makes you a little bit careful. And [George's] being completely obliterated in the campaign because of his brainwashing statement--that makes you go, Whoa, what is that about?"

George had the gaffe to end all gaffes, but Lenore made enough of them to reinforce the lesson. Misstatements about South Africa and Martin Luther King hurt her badly with black voters she had counted on peeling away from Hart. Mitt, meanwhile, learned that politics is truly rough and tumble. In July 1970, a man with a cream pie in his hand made a run at Mitt at the Imlay City Centennial. The man missed, but a photograph in that week's Lapeer County Press caught Mitt, with a large LENORE button on his shirt, in mid-dive across the lap of a local notable. "Mitt Romney does not want a pie in the face," the caption read.