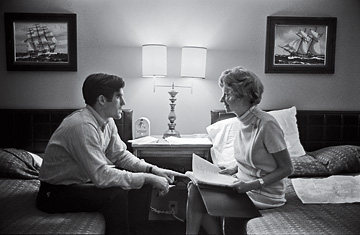

On the campaign trail during his mother's Senate bid, Mitt and Lenore strategize in a hotel room

(8 of 11)

Huber's insurgent campaign nearly toppled Lenore, who eked out a 52%-48% victory in the August primary. "She never really recovered from that," says Ballenger, also the longtime editor of Inside Michigan Politics. Recalled Peterson: "Those who had promised to help Lenore Romney in the beginning suddenly were very busy elsewhere."

On the stump, Lenore acknowledged that her political identity was a work in progress. "I'm trying to become Lenore, the individual, and not Lenore, the wife of George Romney," she told the Grand Rapids Press for a July 15, 1970, story. But she had all her old strengths as a campaigner, shaking hands with a chimpanzee at the Ottawa County Fair, playing Ping-Pong at the Salvation Army in Detroit and gamely venturing, as a teetotaling Mormon, into Zehnder's Hofbruhaus in Frankenmuth. Burned by the bossism charge, her campaign pushed George offstage. The political buttons and banners said simply lenore.

She also developed a more confident voice on policy. "Let's get out of Vietnam as soon as we can," she said at the Michigan Republican convention in Detroit on Aug. 29. On crime, she said, "We can see that people who should be taken away from society are put away from society for a while, but then we must help rehabilitate them." She spoke in dire terms about threats to the environment, blaming Michigan's most powerful employers--and the voters themselves. "Yes, the automobile industry is at fault," she said. "Yes, the paper industry. Yes, the atomic testing and all the rest of it. But we've dumped our beer cans. We have bought the detergents that can't be dissolved. We have been part of the problem and still are."

Lenore had her own version of Romneycare, calling for a national health plan in the long term and an interim insurance program for "all Americans who wish or need to participate." Compared with other industrial nations, she noted, "we rank 13th in deaths of infants in the first year of life, seventh in percentage of mothers who die in childbirth, 18th in the life expectancy of males, 11th in the life expectancy of females." All the countries with better records, she added, "have some form of a national health plan."

On abortion, her unpublished position paper read, "The ultimate decision is left to the woman" because it is "more important to lessen the physical and mental dangers ... and remove the criminal element, than it is to attempt legislated morality." Look quoted her saying categorically, in October 1970, "I'm for legalized abortions," but she also told the Detroit Free Press that year, "I don't think abortion should be used as a birth control measure. We should prevent pregnancies rather than abort them."

A campaign film embraced traditional views of womanhood ("She's not only bright, but she is very attractive," said Bob Hope in one of many such celebrity endorsements) but subverted them enough to justify an independent run for the Senate. In her first appearance onscreen, sitting demurely on a flowered couch, she asked, "Why would a woman like me want to get into politics?"