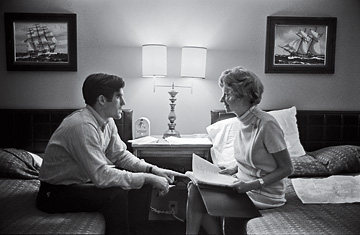

On the campaign trail during his mother's Senate bid, Mitt and Lenore strategize in a hotel room

(6 of 11)

George Romney, meanwhile, charged ahead. He awoke at dawn and often earlier, first to procure his daily rose for Lenore and then, rain or shine, to race through a regimen that he called compact golf. Depending on the light, he would play three to six balls at once, clutching only a 2-iron and running from hole to hole. When it snowed, he used red balls. "I can do six holes with four balls in an hour," he told Life magazine in 1967.

George's politics were equally brawny and improvised. For most of the 1960s, he reigned over Michigan with a buoyant charm and an exuberance for combat that bordered on physical. When state-senate majority leader Emil Lockwood told the governor in 1967 that his tax proposals were dead, recalls former state senator Bill Ballenger, George seized Lockwood's jacket with such force that he "literally ripped the lapels off." A contemporary news account said George growled, "They're not dead!" Michigan passed its first income tax that year.

Donald Riegle Jr., then a 28-year-old Republican wunderkind making his first bid for Congress, watched in amazement on Labor Day 1966 as George crashed the annual picnic of the United Auto Workers in Flint. The union's election-year motto was "Make it emphatic, vote straight Democratic." Unwelcome at the gate, George climbed a six-foot fence from a farmer's adjacent field and "went right on in to the picnic," Riegle says. "George, he could be like a bull in a china shop. If he decided he was going to go over that fence, it wouldn't matter if it was 12 feet high."

George won a third term that year, by his biggest margin ever, and soon began to look like a serious prospect for President. A Gallup poll showed him as the front runner for the GOP nomination--8 points ahead of Richard Nixon, his nearest rival--and a Harris poll had him beating Lyndon Johnson in the general election. But his penchant for speaking off the cuff caught up with him on Aug. 31, 1967. George had changed his mind about the Vietnam War, well ahead of the public. Lou Gordon, host of WKBD television's Hot Seat, asked George to reconcile his previous declaration that the war was "morally right and necessary."

"When I came back from Vietnam, I'd just had the greatest brainwashing that anybody can get," George replied, speaking of a fact-finding trip with fellow governors in 1965 for briefings that touted progress in the war. "Not only by the generals but also by the diplomatic corps over there. And they do a very thorough job." The word brainwashing made him a laughingstock. "A light rinse would have been sufficient," remarked Democratic candidate Eugene McCarthy. George dropped 10 points in the next Gallup poll, and then the bottom fell out. By the time he withdrew from the race on Feb. 28, Nixon had pulled ahead by 42 points. "It was a fatal, self-inflicted wound," Riegle says. "And of course, he thought that was terribly unfair. It made him, I think, quite an angry man. He never got over that, and I don't think Mitt ever got over it."

At the Republican Convention in Miami Beach that summer, George refused to release his delegates to Nixon. Lenore wrote to her friend Marilyn Siebert on Aug. 14 with sardonic understatement, "I will admit, privately, the ticket does not stir me to wildest enthusiasm."