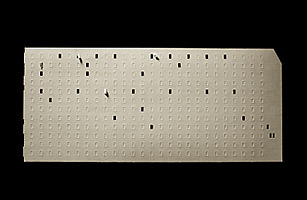

A Florida ballot with four hanging chads, which was considered an overvote

The late evening of Dec. 12, 2000, will long be remembered as the night the Supreme Court five members, anyway selected a President of the United States. It was one of those clear, crisp nights when the Capitol dome blazes so brilliantly in its floodlit glory that it almost seems to vibrate. Meanwhile, tiny by comparison, reporters stood on the Supreme Court steps paging frantically through the momentous opinion, trying to decipher it on live TV. No part of the scene fit with any other. The imposing permanence of the monumental buildings clashed with the unseemly hastiness of the announcement. The austere reflection implicit in the rule of law was undercut by the improvisations and open disagreements in the court's opinion. The orderly lines of mass communication were tangled in the mass confusion.

Ten years later, we know what was on those ballots that Al Gore wanted desperately to have counted. An independent research organization examined every last one, and whether Gore or George W. Bush won more of them was never going to be a matter of fact only interpretation. The margin of victory was more than filled with improperly, mistakenly, carelessly or ambiguously marked ballots. If the election had not been decided by the high court, it would have been decided by Congress through a process laid out by the Constitution. The result would have been close and bitter and would probably have gone to Bush. In other words, we would have wound up very close to the spot we landed in.

But while that surreal night did not alter the path of history, in retrospect it looks less like an ending than an omen of official dysfunction and institutional failure. We learned the hard way that the ballot box is not necessarily a reliable means of measuring votes, and this proved to be the first of many sadly similar lessons: That law enforcement is not a very effective way to stop hijackers. That spy agencies don't really know what's going on inside hostile regimes. That one crafty old zealot can outwit a whole army sent to hunt him down. That engineers don't always build sound levees, nor bankers issue sound loans.

Again and again, the system was tested and the system failed: 9/11, WMD, Katrina, subprime, BP. Time has shown that the Florida recount was the drum major in a parade of naked emperors. Partisans Democrats as well as Republicans drew from Florida's botched election the simple message that the other side can never be trusted. Implacably treacherous, the other side will stop at nothing. And we've seen that this conclusion breeds, at the margins, years of vitriol and conspiracy mongering. Away from the margins, in the middle ground where neither side looks very appealing, the lack of trust fosters a suspicion that we now have a government of the feckless, by the crooked, for the connected.

To see the Florida story in those terms is to see it as melodrama: a lurid pageant of good guys vs. villains with Liberty herself tied to the train tracks. But the same story can be read as a more nuanced and genuine drama — a tale of mixed motives and tragic flaws, the vanity of human wishes and the danger of overconfidence in any system or device or idea wrought by mortals. Maybe the meaning of the Florida fiasco was not only that our institutions deliver too little, but also that we had come to expect too much.

Anything but Simple

It began with a failure of the media. The Delphic voices of the broadcast news networks first called Florida, the key to victory, for Gore, then for Bush, before limply admitting that it was too close to say. The next morning, the Florida sun rose on the preposterous notion that Palm Beach County, a bastion of liberal Democrats, had given a decisive share of its votes to conservative provocateur Patrick J. Buchanan. To explain how that could be, America was introduced to the butterfly ballot an invention, we soon learned, intended to simplify the voting process by making it more complicated. The story then unfolded in courts and counting rooms, each twist and turn a further step into the unknown and the unlikely. The conflicts of interest were cartoonishly glaring. Would you believe that the person in charge of certifying votes was a state chairman of the Bush campaign, while the person in charge of enforcing state laws was chairman of the Gore campaign? How about the governor being Bush's younger brother? The language of the drama was farcical: dangling chads, the Brooks Brothers riot, the Thanksgiving stuffing. Sleepy Tallahassee, capital of the crisis, was by the end as thick with freaks and onlookers as a carnival midway.