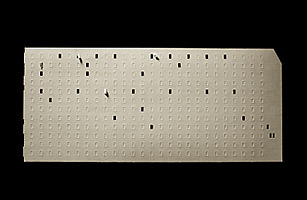

A Florida ballot with four hanging chads, which was considered an overvote

(2 of 3)

The action escalated for more than a month, until, in a bold order by the narrowest of margins, the Florida Supreme Court instructed 67 counties to examine their ballots under the supervision of a Florida district court judge in Tallahassee. Within hours, the U.S. Supreme Court brought the process to a halt, setting the stage for a painfully fractured high court to decide the dispute in Bush's favor.

It's likely that no legal battle ever consumed as many hours and as much energy in so short a span of days. The two sides argued in every available forum — not least the court of public opinion. But they were in striking agreement on one point: both the Gore and Bush teams insisted that the problem in Florida was really very simple. In daily dueling press conferences, the warring sides adopted identical tones of voice — namely, the exaggerated calm of a kindergarten teacher trying for the umpteenth time to explain to squirming Tommy the difference between b and d.

For Bush, who held a tiny lead in the reported votes, the simple fact was that after a count, a recount and yet another manual recount, he had won the state of Florida — and therefore the election. For Gore, who knew that thousands of ballots had been rejected by voting machines and had not been examined by hand, simple fairness demanded that every legally cast vote should be counted.

There were good strategic reasons for these messages. The fact that Bush began the recount with a lead no matter how tiny ordained that his team would defend the status quo, while Gore's team, because it was trailing, had no choice but to shake things up. The best way to understand the recount, Gore's chief legal strategist, Ron Klain, explains, is that Gore had only one path to victory — a court-ordered recount — while Bush had two paths to victory. He won if the courts issued favorable rulings for him or if the courts did nothing at all.

But beneath these simple messages lay intricate issues. What sounded like clarity in the press conferences was, in reality, highly misleading. Florida's election laws had been written primarily to resolve local disputes, not a deadlocked presidential election. So when Bush observed that the ballots had been counted, recounted and counted again, he glossed over the really thorny matter: What did it mean to "count" or "recount" votes? Must they be examined under magnifying glasses, as they were by a Broward County official immortalized in an iconic photograph of the Florida controversy? Or was it enough, as other officials believed, just to run the punch cards through the machines a second time? Not only was there no agreement among Florida's local jurisdictions; there wasn't even any established legal means for forcing the local authorities onto the same page.

Something similar was true of Gore's message. In pleading that every legal vote be counted, he too skipped over the meat of the matter: What exactly is a vote, what makes it legal, and who decides (and how)? Former solicitor general Theodore Olson, who argued Bush's case at the Supreme Court, still believes that the best rules were the ones published in the polling places when the doors opened on Election Day. "The rules respecting the counting of ballots had to be the rules and procedures in place at the time of the election," he says, "and could not be changed after the fact."

Everyone could be satisfied only as long as no decision was reached. But someone had to decide, and for a few hours in early December 2000, the job rested with Judge Terry Lewis of the Florida district court. Until the U.S. Supreme Court intervened, Lewis was the judge assigned to implement the process ordered by the state supreme court. To this day, he remains confident that he could have examined all the disputed ballots and ruled on each of them in plenty of time to settle the election. "I would not have agonized," he says. "The standard would have been, Could I tell the clear intent of the voter? And if I had to sit and contemplate, then the intent would not be clear."

Once again, simple. But as Lewis continues reminiscing, he mentions that he had planned to expand the parameters of the state supreme court order without consulting the justices. And he had decided to conduct his examination of the ballots without allowing lawyers for the candidates to watch him. "Either you trust me or you don't," he says. That's what judges do: they make judgment calls.