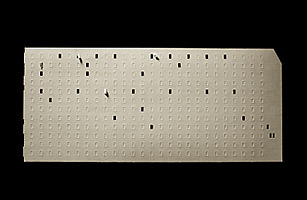

A Florida ballot with four hanging chads, which was considered an overvote

(3 of 3)

Of course, it could never have gone like that. The stakes were too high, the publicity too intense, the suspicion too rampant. No individual judge was going to disappear into an office at the Leon County courthouse and emerge later to say, Trust me, this is your new President.

Florida revealed to the public a fact that politicians have known forever. Elections are approximations, and a certain amount of confusion, error, malfunction and even fraud inevitably creeps into far-flung and myriad polling places. Voters ignore or misinterpret instructions. Volunteer poll workers misapply rules. Machines fail, sometimes in subtle ways that aren't noticed. None of this matters until the margin of victory drops to nil, and by then it's too late to fix it.

This unsatisfying reality of the Florida election was documented by a group of big media companies in 2001. The group commissioned the impeccably independent National Opinion Research Center to examine all the ballots that failed to register as votes when run through counting machines. This included the ballots that showed no recognizable vote for President (the undervotes) and the ballots that showed more than one vote for President (the overvotes). The project took months to plan and execute, and its conclusions were a wash of ambiguity. When certain standards were applied to the ballots, Bush finished with the most votes. When others were applied, Gore prevailed. An extremely detailed report of these findings is available online, and the one thing it proves beyond dispute is that Florida was not simple.

"When you examine the overvotes, Gore won by thousands," said the Washington Post's Dan Keating, who was one of the project's leaders. These ballots include, for example, a large number of optical scanning cards on which voters filled in the bubble to indicate a vote for Gore, then added his name to the write-in line, thereby double-voting. The machines rejected these ballots because they clearly violated the instructions that voters were to follow. "If you use the standard of a legal ballot — which is obviously a very reasonable standard — then the results were different," Keating concluded.

Great Expectations

The point is not that the election of 2000 was decided correctly or even in the best possible way. The point is that there was no perfect solution, no simple answer. And no matter how you felt about the outcome, it was an unappealing spectacle, frantic and slapdash. Election boards were flummoxed by punch cards. State officials dressed partisan power grabs in flimsy patriotic rationales. And the U.S. Supreme Court split along party lines to produce an opinion so badly flawed that even the majority said it could never be used as a foundation for future cases.

But the episode was a sign of things to come in this way too: the people who paved the way to failure escaped harsh judgment compared with the unlucky folks left to clean up. Buried in the debris was the fact that Gore was the first candidate in a generation to lose his home state, which could have put him over the top. Other factors received even less attention: the overconfidence of the Bush campaign in Florida; the failure of parties, election boards and local governments to test ballot designs, maintain voting machines and teach people how to cast a legal vote; the scant attention paid by the legislature to writing robust election laws.

In other words, people took for granted that nothing bad would happen, which is a luxury of living in a singularly fortunate land. Expecting only good things was expecting too much. By failing to prepare for trouble, we both encouraged trouble and left ourselves few tools when it came. When you think about it, that has been true of the whole series of disheartening events that followed Florida. We took for granted that terrorists wouldn't cross the oceans, that Afghanistan and Iraq would be cakewalks, that no hurricane would hit New Orleans, that home prices could only go up. There were warnings, yes, but the warnings were largely ignored.

Not many people were able to rise above their own partisan preferences during the Florida recount battle, but Florida Justice Leander Shaw was among the few. In early December, he voted to halt the process. "All the king's horses and all the king's men could not get a few thousand ballots counted," Shaw wrote in a subsequent opinion. "The explanation, however, is timeless. We are a nation of men and women and, although we aspire to lofty principles, our methods at times are imperfect." That's human nature, and it will not change — and we would be wise to start preparing for it.