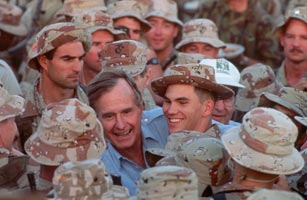

President George Bush shakes hands with US Army troops in Saudi Arabia during the Gulf War on Thanksgiving Day, 1990

During the heady days after his Inauguration, George Bush delighted in leading guests on private tours of the White House. He often paused in the hideaway office beside his bedroom before a favorite painting of Abraham Lincoln conferring with his generals during the Civil War. "He was tested by fire," Bush would muse, "and showed his greatness." And to one friend, Bush wondered aloud how he might be tested, whether he too might be one of the handful of Presidents destined to change the course of history.

On Aug. 1 he found out.

It was about 8 p.m. in Washington and Bush had gone upstairs for the evening, when an aide brought an urgent message from the White House Situation Room. Iraq had invaded Kuwait. At first, most diplomatic and intelligence analysts believed Saddam Hussein would confine his thrust to long-disputed border areas. But as Bush followed the latest reports — from the CIA and CNN — Iraqi tanks churned into the Kuwaiti capital, forcing the royal family to flee. It was a full-blown takeover.

Next morning the world was waiting to hear what Bush had to say about that blatant act of aggression. At 8, just before an emergency session of the National Security Council, he invited reporters in for a brief exchange. "We're not discussing intervention," Bush insisted. "I'm not contemplating such action." He stammered a bit, as he often does when he is tired — or when he does not believe what he is saying. This time it was both.

As Bush would later recall, he had made an "almost instantaneous" judgment that the U.S. must intervene. In fact, even before sunup on Aug. 2, he had begun to move against Iraq. When Bush awoke shortly after 5, his National Security Adviser, Brent Scowcroft, was at the President's bedroom door. He immediately got Bush's signature on a pair of executive orders freezing the assets of Iraq and Kuwait in the U.S. and prohibiting trade. The two men then resumed the discussions they had begun the night before, talking through their options: Let's get the allies to follow us on the asset freeze. Buck up the other Arabs to condemn Iraq. Keep Israel quiet. Get the Soviets on board. Work the U.N. Go for economic sanctions.

Both men were determined to do more — much more. But Bush — obsessed with secrecy as always — would mask his inclinations, at least initially, even at his first NSC meeting on the crisis.

At that session, once the reporters had been herded out and fresh coffee had been poured, the atmosphere was relaxed and matter-of-fact. One by one, Bush's top generals and diplomats, spymasters and energy experts reeled off their analyses. The prevailing attitude among the group, recalled one White House official, was "Hey, too bad about Kuwait, but it's just a gas station, and who cares whether the sign says Sinclair or Exxon?" Anyway, what can we do? Doesn't Iraq have the Middle East's largest army, and aren't we a long way from the scene?

There was little sense that big U.S. interests were at stake — until the President spoke. He asked a simple question that decisively shifted the debate: "What happens if we do nothing?"

A Dog That Would Bite

That question could have been Bush's graven motto, at least before 1990, and it still could be in all but foreign affairs. During the first 18 months of his presidency, communism collapsed, the cold war ended, freedom spread across the Soviet empire, and Nelson Mandela's release after 27 years in South African prisons raised the prospect that apartheid might soon come tumbling down. Except when Bush invaded Panama to remove an irritating dictator, he had mostly sat and applauded politely as these momentous events unfolded. His rationale was sound enough: when things are going your way, don't get in the way.

Bush's instincts were entirely different in the gulf crisis. This time, letting events take their course would not suffice. This was the moment for which he had spent a lifetime preparing, the epochal event that would bear out his campaign slogan, "Ready to be a great President from Day 1." And Bush's instincts were only confirmed as the consequences of allowing Iraq to swallow Kuwait became clear.

If Iraq's aggression succeeded, an emboldened Saddam might send his troops into Saudi Arabia or intimidate the lightly defended petrokingdom, as well as its neighbors, into obeying his dictates. Fifty-six percent of the world's oil supplies would come under the sway of a ruthless dictator who is trying to amass a force of long-range missiles that could hit every state in the region, including Israel, with chemical, biological and — in a few years — nuclear weapons. Every petty tyrant who wanted to redraw the map of the world by force, who hated a neighbor or coveted that neighbor's goods, would have learned a lesson: in the post-cold war world, aggression pays.